- Print this page

- Share this page

Download a PDF of this document in full.

Foreword

The State Insurance Regulatory Authority has reissued the 4th edition of the NSW workers compensation guidelines for the evaluation of permanent impairment (catalogue no. WC00970) (the Guidelines) for assessing the degree of permanent impairment arising from an injury or disease within the context of workers’ compensation. When a person sustains a permanent impairment, trained medical assessors must use the Guidelines to ensure an objective, fair and consistent method of evaluating the degree of permanent impairment.

The reissued Guidelines have been made to include some minor changes including changes consequent to the enactment of the Personal Injury Commission Act 2020 (PIC Act). No changes are made to the provisions in these guidelines relating to the evaluation of permanent impairment as developed in consultation with the medical Colleges under s 377(2) of the Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 and as set out in cl 13 of the Guidelines.

The Guidelines are based on a template that was developed through a national process facilitated by Safe Work Australia. They were initially developed for use in the NSW system and incorporate numerous improvements identified by the then WorkCover NSW Whole Person Impairment Coordinating Committee over 13 years of continuous use. Members of this committee and of the South Australia Permanent Impairment Committee (see list in Appendix 2) dedicated many hours to thoughtfully reviewing and improving the Guidelines. This work is acknowledged and greatly appreciated.

The methodology in the Guidelines is largely based on the American Medical Association’s Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, 5th Edition (AMA5). The AMA guides are the most authoritative and widely used in evaluating permanent impairment around the world. Australian medical specialists representing Australian medical associations and colleges have extensively reviewed AMA5 to ensure it aligns with clinical practice in Australia.

The Guidelines consist of an introductory chapter followed by chapters dedicated to each body system.

The Introduction is divided into three parts. The first outlines the background and development of the Guidelines, including reference to the relevant legislative instrument that gives effect to the Guidelines. The second covers general assessment principles for medical practitioners applying the Guidelines in assessing permanent impairment resulting from work-related injury or disease. The third addresses administrative issues relating to the use of the Guidelines.

As the template national guideline has been progressively adapted from the NSW Guideline and is to be adopted by other jurisdictions, some aspects have been necessarily modified and generalised. Some provisions may differ between different jurisdictions. For further information, please see the Comparison of Workers’ Compensation Arrangements in Australia and New Zealand report, which is available on Safe Work Australia’s website.

Publications such as this only remain useful to the extent that they meet the needs of users and those who sustain a permanent impairment. It is, therefore, important that the protocols set out in the Guidelines are applied consistently and methodically. Any difficulties or anomalies need to be addressed through modification of the publication and not by idiosyncratic reinterpretation of any part. All queries on the Guidelines or suggestions for improvement should be addressed to SIRA at contact@sira.nsw.gov.au.

Part 1 - Intent and legislative basis for these guidelines

1.1 The reissued 4th edition of the NSW workers compensation guidelines for the evaluation of permanent impairment (catalogue no. WC00970) (the Guidelines) is made under s376 of the Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 (WIMWC Act) and commence on 1 March 2021 when the Personal Injury Commission is established. The Guidelines are to be used within the NSW workers compensation system to evaluate permanent impairment arising from work-related injuries and diseases.

The Guidelines adopt the 5th edition of the American Medical Association’s Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment (AMA5) in most cases. Where there is any deviation, the difference is defined in the Guidelines and the procedures detailed in each section are to prevail.

1.2 The Guidelines replace the WorkCover Guides for the evaluation of permanent impairment, 4th edition, which was issued on 1 April 2016, and subject to the PIC Act apply to assessments of permanent impairment conducted on or after 1 March 2021.

When conducting a permanent impairment assessment in accordance with the Guidelines, assessors are required to use the version current at the time of the assessment.

1.3 The Guidelines are based on a template that was developed through a national process facilitated by Safe Work Australia. The template national guideline is based on similar guidelines developed and used extensively in the NSW workers compensation system. Consequently, provisions in the Guidelines are the result of extensive and in-depth deliberations by groups of medical specialists convened to review AMA5 in the Australian workers compensation context. In NSW it is a requirement under s377(2) of the WIMWC Act that the guidelines are developed in consultation with relevant medical colleges. The groups that contributed to the development of the Guidelines is acknowledged and recorded at Appendix 2. The template national guideline has been adopted for use in multiple Australian jurisdictions.

1.4 Use of the Guidelines is monitored by the jurisdictions that have adopted it. The Guidelines may be reviewed if significant anomalies or insurmountable difficulties in their use become apparent.

1.5 The Guidelines are intended to assist a suitably qualified and experienced medical practitioner in assessing a claimant’s degree of permanent impairment.

Part 2 - Principles of assessment

1.6 The following is a basic summary of some key principles of permanent impairment assessments:

a. Assessing permanent impairment involves clinical assessment of the claimant as they present on the day of assessment taking account the claimant’s relevant medical history and all available relevant medical information to determine:

- whether the condition has reached Maximum Medical Improvement (MMI)

- whether the claimant’s compensable injury/condition has resulted in an impairment

- whether the resultant impairment is permanent

- the degree of permanent impairment that results from the injury

- the proportion of permanent impairment due to any previous injury, pre-existing condition or abnormality,

- if any, in accordance with diagnostic and other objective criteria as outlined in these Guidelines.

b. Assessors are required to exercise their clinical judgement in determining a diagnosis when assessing permanent impairment and making deductions for pre-existing injuries/conditions.

c. In calculating the final level of impairment, the assessor needs to clarify the degree of impairment that results from the compensable injury/condition. Any deductions for pre-existing injuries/conditions are to be clearly identified in the report and calculated. If, in an unusual situation, a related injury/condition has not previously been identified, an assessor should record the nature of any previously unidentified injury/condition in their report and specify the causal connection to the relevant compensable injury or medical condition.

d. The referral for an assessment of permanent impairment is to make clear to the assessor the injury or medical condition for which an assessment is sought – see also paragraphs 1.43 and 1.44 in the Guidelines.

1.7 Medical assessors are expected to be familiar with chapters 1 and 2 of AMA5, in addition to the information in this introduction.

1.8 The degree of permanent impairment that results from the injury/condition must be determined using the tables, graphs and methodology given in the Guidelines and the AMA5, where appropriate.

1.9 The Guidelines may specify more than one method that assessors can use to establish the degree of a claimant’s permanent impairment. In that case, assessors should use the method that yields the highest degree of permanent impairment. (This does not apply to gait derangement – see paragraphs 3.5 and 3.10 in the Guidelines).

1.10 AMA5 is used for most body systems, with the exception of psychiatric and psychological disorders, chronic pain, and visual and hearing injuries.

1.11 AMA5 Chapter 14, on mental and behavioural disorders, has been omitted. The Guidelines contain a substitute chapter on the assessment of psychiatric and psychological disorders which was written by a group of Australian psychiatrists.

1.12 AMA5 Chapter 18, on pain, is excluded entirely at the present time. Conditions associated with chronic pain should be assessed on the basis of the underlying diagnosed condition, and not on the basis of the chronic pain. Where pain is commonly associated with a condition, an allowance is made in the degree of impairment assigned in the Guidelines. Complex regional pain syndrome should be assessed in accordance with Evaluation of permanent impairment arising from chronic pain in the Guidelines.

1.13 On the advice of medical specialists (ophthalmologists), assessments of visual injuries are conducted according to the American Medical Association’s Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, 4th Edition (AMA4).

1.14 The methodology for evaluating permanent impairment due to hearing loss is in Hearing Loss of the Guidelines, with some reference to AMA5 Chapter 11 (pp 245–251) and also the tables in the National Acoustic Laboratories (NAL) Report No. 118, Improved Procedure for Determining Percentage Loss of Hearing, January 1988.

1.15 Assessments are only to be conducted when the medical assessor considers that the degree of permanent impairment of the claimant is unlikely to improve further and has attained maximum medical improvement. This is considered to occur when the worker’s condition is well stabilised and is unlikely to change substantially in the next year with or without medical treatment.

1.16 If the medical assessor considers that the claimant’s treatment has been inadequate and maximum medical improvement has not been achieved, the assessment should be deferred and comment made on the value of additional or different treatment and/or rehabilitation – subject to paragraph 1.34 in the Guidelines.

1.17 Impairments arising from the same injury are to be assessed together. Impairments resulting from more than one injury arising out of the same incident are to be assessed together to calculate the degree of permanent impairment of the claimant.

1.18 The Combined Values Chart in AMA5 (pp 604–06) is used to derive a percentage of whole person impairment (WPI) that arises from multiple impairments. An explanation of the chart’s use is found on pp 9–10 of AMA5. When combining more than two impairments, the assessor should commence with the highest impairment and combine with the next highest and so on.

1.19 The exception to this rule is in the case of psychiatric or psychological injuries. Where applicable, impairments arising from primary psychological and psychiatric injuries are to be assessed separately from the degree of impairment that results from any physical injuries arising out of the same incident. The results of the two assessments cannot be combined.

1.20 In the case of a complex injury, where different medical assessors are required to assess different body systems, a ‘lead assessor’ should be nominated to coordinate and calculate the final degree of permanent impairment as a percentage of WPI resulting from the individual assessments.

1.21 Psychiatric and psychological injuries in the NSW workers compensation system are defined as primary psychological and psychiatric injuries in which work was found to be a substantial contributing factor.

1.22 A primary psychiatric condition is distinguished from a secondary psychiatric or psychological condition, which arises as a consequence of, or secondary to, another work related condition (eg depression associated with a back injury). No permanent impairment assessment is to be made of secondary psychiatric and psychological impairments. As referenced in section Multiple impairments, impairments arising from primary psychological and psychiatric injuries are to be assessed separately from the degree of impairment that results from physical injuries arising out of the same incident. The results of the two assessments cannot be combined.

1.23 AMA5 (p 11) states:

Given the range, evolution and discovery of new medical conditions, these Guidelines cannot provide an impairment rating for all impairments… In situations where impairment ratings are not provided, these Guidelines suggest that medical practitioners use clinical judgment, comparing measurable impairment resulting from the unlisted condition to measurable impairment resulting from similar conditions with similar impairment of function in performing activities of daily living.’ The assessor must stay within the body part/region when using analogy.The assessor’s judgment, based upon experience, training, skill, thoroughness in clinical evaluation, and ability to apply the Guidelines criteria as intended, will enable an appropriate and reproducible assessment to be made of clinical impairment.

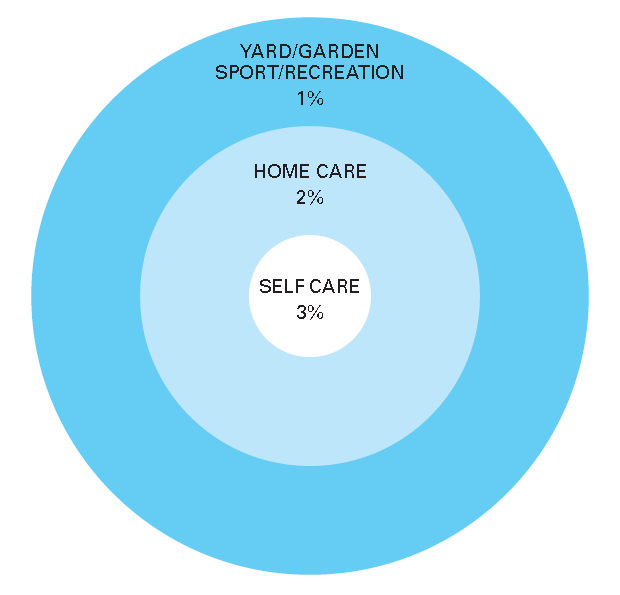

1.24 Many tables in AMA5 (eg in the spine section) give class values for particular impairments, with a range of possible impairment values in each class. Commonly, the tables require the assessor to consider the impact of the injury or illness on activities of daily living (ADL) in determining the precise impairment value. The ADL which should be considered, if relevant, are listed in AMA5 Table 1–2 (p 4). The impact of the injury on ADL is not considered in assessments of the upper or lower extremities.

1.25 The assessment of the impact of the injury or condition on ADL should be verified, wherever possible, by reference to objective assessments – for example, physiotherapist or occupational therapist functional assessments and other medical reports.

1.26 Occasionally the methods of the Guidelines will result in an impairment value which is not a whole number (eg an assessment of peripheral nerve impairment in the upper extremity). All such values must be rounded to the nearest whole number before moving from one degree of impairment to the next (eg from finger impairment to hand impairment, or from hand impairment to upper extremity impairment) or from a regional impairment to a WPI. Figures should also be rounded before using the combination tables. This will ensure that the final WPI will always be a whole number. The usual mathematical convention is followed where rounding occurs – values less than 0.5 are rounded down to the nearest whole number and values of 0.5 and above are rounded up to the next whole number. The method of calculating levels of binaural hearing loss is shown in Hearing impairment, paragraph 9.15, Chapter 9 in the Guidelines.

1.27 The degree of permanent impairment resulting from pre-existing impairments should not be included in the final calculation of permanent impairment if those impairments are not related to the compensable injury. The assessor needs to take account of all available evidence to calculate the degree of permanent impairment that pre-existed the injury.

1.28 In assessing the degree of permanent impairment resulting from the compensable injury/condition, the assessor is to indicate the degree of impairment due to any previous injury, pre-existing condition or abnormality. This proportion is known as ‘the deductible proportion’ and should be deducted from the degree of permanent impairment determined by the assessor. For the injury being assessed, the deduction is 1/10th of the assessed impairment, unless that is at odds with the available evidence.

1.29 Assessments of permanent impairment are to be conducted without assistive devices, except where these cannot be removed. The assessor will need to make an estimate as to what is the degree of impairment without such a device, if it cannot be removed for examination purposes. Further details may be obtained in the relevant sections of the Guidelines.

1.30 Impairment of vision should be measured with the claimant wearing their prescribed corrective spectacles and/or contact lenses, if this was usual for them before the injury. If, as a result of the injury, the claimant has been prescribed corrective spectacles and/or contact lenses for the first time, or different spectacles and/or contact lenses than those prescribed pre-injury, the difference should be accounted for in the assessment of permanent impairment.

1.31 In circumstances where the treatment of a condition leads to a further, secondary impairment, other than a secondary psychological impairment, the assessor should use the appropriate parts of the Guidelines to evaluate the effects of treatment, and use the Combined Values Chart (AMA5, pp 604–06) to arrive at a final percentage of WPI.

1.32 Where the effective long-term treatment of an illness or injury results in apparent substantial or total elimination of the claimant’s permanent impairment, but the claimant is likely to revert to the original degree of impairment if treatment is withdrawn, the assessor may increase the percentage of WPI by 1%, 2% or 3%. This percentage should be combined with any other impairment percentage, using the Combined Values Chart. This paragraph does not apply to the use of analgesics or anti-inflammatory medication for pain relief.

1.33 Where a claimant has declined treatment which the assessor believes would be beneficial, the impairment rating should be neither increased nor decreased – see paragraph 1.35 for further details.

1.34 If the claimant has been offered, but has refused, additional or alternative medical treatment that the assessor considers likely to improve the claimant’s condition, the medical assessor should evaluate the current condition without consideration of potential changes associated with the proposed treatment. The assessor may note the potential for improvement in the claimant’s condition in the evaluation report, and the reasons for refusal by the claimant, but should not adjust the level of impairment on the basis of the claimant’s decision.

1.35 Similarly, if a medical assessor forms the opinion that the claimant’s condition is stable for the next year, but that it may deteriorate in the long term, the assessor should make no allowance for this deterioration.

1.36 AMA5 (p 19) states:

Consistency tests are designed to ensure reproducibility and greater accuracy. These measurements, such as one that checks the individual’s range of motion are good but imperfect indicators of people’s efforts. The assessor must use their entire range of clinical skill and judgment when assessing whether or not the measurements or test results are plausible and consistent with the impairment being evaluated. If, in spite of an observation or test result, the medical evidence appears insufficient to verify that an impairment of a certain magnitude exists, the assessor may modify the impairment rating accordingly and then describe and explain the reason for the modification in writing.

This paragraph applies to inconsistent presentation only.

1.37 As a general principle, the assessor should not order additional radiographic or other investigations purely for the purpose of conducting an assessment of permanent impairment.

1.38 However, if the investigations previously undertaken are not as required by the Guidelines, or are inadequate for a proper assessment to be made, the medical assessor should consider the value of proceeding with the evaluation of permanent impairment without adequate investigations.

1.39 In circumstances where the assessor considers that further investigation is essential for a comprehensive evaluation to be undertaken, and deferral of the evaluation would considerably inconvenience the claimant (eg when the claimant has travelled from a country region specifically for the assessment), the assessor may proceed to order the appropriate investigations provided that there is no undue risk to the claimant. The approval of the referring body for the additional investigation will be required to ensure that the costs of the test are met promptly.

Part 3 - Administrative process

1.40 An assessor will be a registered medical practitioner recognised as a medical specialist.

- ‘Medical practitioner’ means a person registered in the medical profession under the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (NSW) No. 86a, or equivalent Health Practitioner Regulation National Law in their jurisdiction with theAustralian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency.

- ‘Medical specialist’ means a medical practitioner recognised as a specialist in accordance with the Health Insurance Regulations 1975, Schedule 4, Part 1, who is remunerated at specialist rates under Medicare.

The assessor will have qualifications, training and experience relevant to the body system being assessed. The assessor will have successfully completed requisite training in using the Guidelines for each body system they intend on assessing. They will be listed as a trained assessor of permanent impairment for each relevant body system(s) on the SIRA website.

1.41 An assessor may be one of the claimant’s treating practitioners or an assessor engaged to conduct an assessment for the purposes of determining the degree of permanent impairment.

1.42 Information for claimants regarding independent medical examinations and assessments of permanent impairment should be supplied by the referring body when advising of the appointment details.

1.43 On referral, the medical assessor should be provided with all relevant medical and allied health information, including results of all clinical investigations related to the injury/condition in question.

1.44 Most importantly, assessors must have available to them all information about the onset, subsequent treatment, relevant diagnostic tests, and functional assessments of the person claiming a permanent impairment. The absence of required information could result in an assessment being discontinued or deferred. AMA5 Chapter 1, Section 1.5 (p 10) applies to the conduct of assessments and expands on this concept.

1.45 The Guidelines and AMA5 indicate the information and investigations required to arrive at a diagnosis and to measure permanent impairment. Assessors must apply the approach outlined in the Guidelines.

Referrers must consult this publication to gain an understanding of the information that should be provided to the assessor in order to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of impairment.

1.46 A report of the evaluation of permanent impairment should be accurate, comprehensive and fair. It should clearly address the question(s) being asked of the assessor. In general, the assessor will be requested to address issues of:

- current clinical status, including the basis for determining maximum medical improvement

- the degree of permanent impairment that results from the injury/condition, and

- the proportion of permanent impairment due to any previous injury, pre-existing condition or abnormality, if applicable.

1.47 The report should contain factual information based on all available medical information and results of investigations, the assessor’s own history-taking and clinical examination. The other reports or investigations that are relied upon in arriving at an opinion should be appropriately referenced in the assessor’s report.

1.48 As the Guidelines are to be used to assess permanent impairment, the report of the evaluation should provide a rationale consistent with the methodology and content of the Guidelines. It should include a comparison of the key findings of the evaluation with the impairment criteria in the Guidelines. If the evaluation was conducted in the absence of any pertinent data or information, the assessor should indicate how the impairment rating was determined with limited data.

1.49 The assessed degree of impairment is to be expressed as a percentage of WPI.

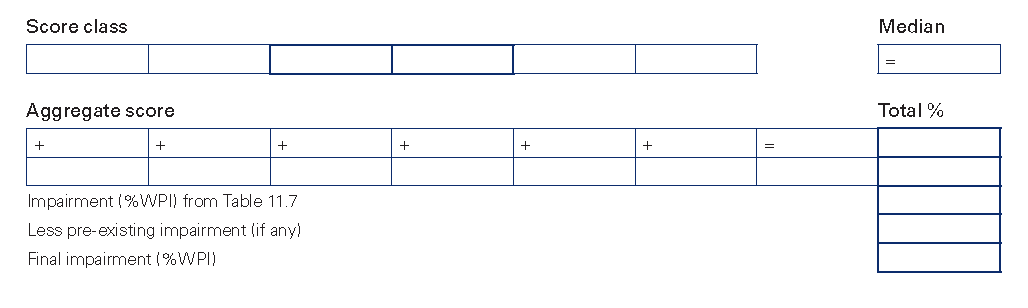

1.50 The report should include a conclusion of the assessor, including the final percentage of WPI. This is to be included as the final paragraph in the body of the report, and not as a separate report or appendix. The report must include a copy of all calculations and a summary table. A template reporting format is provided in the WorkCover Guidelines on independent medical examinations and reports.

1.51 Reports are to be provided within 10 working days of the assessment being completed, or as agreed between the referrer and the assessor.

1.52 The degree of permanent impairment that results from the injury must be determined using the tables, graphs and methodology given in the Guidelines, as presented in the training in the use of the Guidelines and the applicable legislation. If it is not clear that a report has been completed in accordance with the Guidelines, clarification may be sought from the assessor who prepared the report.

1.53 An assessor who is identified as frequently providing reports that are not in accord with the Guidelines, or not complying with other service standards as set by SIRA, may be subject to SIRA performance monitoring procedures and be asked to show cause as to why their name should not be removed from the list of trained assessors on the SIRA website.

1.54 Assessors are referred to the Medical Board of Australia’s Good Medical Practice: A Code of Conduct for Doctors in Australia, 8.7 Medico-legal, insurance and other assessments.

1.55 Assessors are reminded that they have an obligation to act in an ethical, professional and considerate manner when examining a claimant for the determination of permanent impairment.

1.56 Effective communication is vital to ensure that the claimant is well informed and able to maximally cooperate in the process. Assessors should:

- ensure that the claimant understands who the assessor is and the assessor’s role in the evaluation

- ensure that the claimant understands how the evaluation will proceed

- take reasonable steps to preserve the privacy and modesty of the claimant during the evaluation

- not provide any opinion to the claimant about their claim.

1.57 Complaints received in relation to the behaviour of an assessor during an evaluation will be managed in accordance with the process outlined in the WorkCover Guidelines on independent medical examinations and reports and SIRA performance monitoring procedures.

1.58 Where there is a discrepancy or inconsistency between medical reports that cannot be resolved between the parties, the Personal Injury Commission has the jurisdiction to determine disputes about assessed degree of permanent impairment.

Footnotes

* As of 1 September 2015, the workers compensation insurance regulatory functions of WorkCover NSW have been assumed by the State Insurance Regulatory Authority (SIRA).

AMA5 Chapter 16 (p 433) applies to the assessment of permanent impairment of the upper extremities, subject to the modifications set out below. Before undertaking an impairment assessment, users of the Guidelines must be familiar with:

- the Introduction in the Guidelines

- chapters 1 and 2 of AMA5

- the appropriate chapter(s) of the Guidelines for the body system they are assessing

- the appropriate chapter(s) of AMA5 for the body system they are assessing.

The Guidelines take precedence over AMA5.

Introduction

2.1 The upper extremities are discussed in AMA5 Chapter 16 (pp 433–521). This chapter provides guidelines on methods of assessing permanent impairment involving these structures. It is a complex chapter that requires an organised approach with careful documentation of findings.

2.2 Evaluation of anatomical impairment forms the basis for upper extremity impairment (UEI) assessment. The rating reflects the degree of impairment and its impact on the ability of the person to perform ADL. There can be clinical conditions where evaluation of impairment may be difficult. Such conditions are evaluated by their effect on function of the upper extremity, or, if all else fails, by analogy with other impairments that have similar effects on upper limb function.

The approach to assessment of the upper extremity and hand

2.3 Assessment of the upper extremity mainly involves clinical evaluation. Cosmetic and functional evaluations are performed in some situations. The impairment must be permanent and stable. The claimant will have a defined diagnosis that can be confirmed by examination.

2.4 The assessed impairment of a part or region can never exceed the impairment due to amputation of that part or region. For an upper limb, therefore, the maximum evaluation is 60% whole person impairment (WPI), the value for amputation through the shoulder.

2.5 Range of motion (ROM) is assessed as follows:

- A goniometer or inclinometer must be used, where clinically indicated.

- Passive ROM may form part of the clinical examination to ascertain clinical status of the joint, but impairment should only be calculated using active ROM measurements. Impairment values for degree measurements falling between those listed must be adjusted or interpolated.

- If the assessor is not satisfied that the results of a measurement are reliable, repeated testing may be helpful in this situation.

- If there is inconsistency in ROM, then it should not be used as a valid parameter of impairment evaluation. Refer to paragraph 1.36 in the Introduction.

- If ROM measurements at examination cannot be used as a valid parameter of impairment evaluation, the assessor should then use discretion in considering what weight to give other available evidence to determine if an impairment is present.

2.6 To achieve an accurate and comprehensive assessment of the upper extremity, findings should be documented on a standard form. AMA5 Figures 16-1a and 16-1b (pp 436–37) are extremely useful both to document findings and to guide the assessment process.

2.7 The hand and upper extremity are divided into regions: thumb, fingers, wrist, elbow and shoulder. Close attention needs to be paid to the instructions in AMA5 Figures 16-1a and 16-1b (pp 436–37) regarding adding or combining impairments.

2.8 AMA5 Table 16-3 (p 439) is used to convert upper extremity impairment to WPI. When the Combined Values Chart is used, the assessor must ensure that all values combined are in the same category of impairment (that is WPI, upper extremity impairment percentage, hand impairment percentage and so on). Regional impairments of the same limb (eg several upper extremity impairments) should be combined before converting to percentage WPI. (Note that impairments relating to the joints of the thumb are added rather than combined – AMA5 Section 16.4d ‘Thumb ray motion impairment’, p 454.)

Specific interpretation of AMA5 - the hand and upper extremity impairment of the upper extremity due to peripheral nerve disorders

2.9 If an upper extremity impairment results solely from a peripheral nerve injury, the assessor should not also evaluate impairment(s) from AMA5 Section 16.4 ‘Abnormal motion’ (pp 450–79) for that upper extremity. AMA5 Section 16.5 should be used for evaluating such impairments.

For evaluating peripheral nerve lesions, use AMA5 Table 16-15 (p 492) together with AMA5 tables 16-10 and 16-11 (pp 482 and 484).

The assessment of carpal tunnel syndrome post-operatively is undertaken in the same way as assessment without operation.

2.10 When applying AMA5 tables 16-10 (p 482) and 16-11 (pp 482 and 484) the examiner must use clinical judgement to estimate the appropriate percentage within the range of values shown for each severity grade. The maximum value is not applied automatically.

Impairment due to other disorders of the upper extremity

2.11 AMA5 Section 16.7 ‘Impairment of the upper extremity due to other disorders’ (pp 498–507) should be used only when other criteria (as presented in AMA5 sections 16.2–16.6, pp 441–98) have not adequately encompassed the extent of the impairments. Impairments from the disorders considered in AMA5 Section 16.7 are usually estimated using other criteria. The assessor must take care to avoid duplication of impairments.

2.12 AMA5 Section 16.7 (impairment of the upper extremities due to other disorders) notes ‘the severity of impairment due to these disorders is rated separately according to Table 16-19 through 16-30 and then multiplied by the relative maximum value of the unit involved, as specified in Table 16-18’. This statement should not include tables 16-25 (carpal instability), 16-26 (shoulder instability) and 16-27 (arthroplasty), noting that the information in these tables is already expressed in terms of upper extremity impairment.

2.13 Strength evaluation, as a method of upper extremity impairment assessment, should only be used in rare cases and its use justified when loss of strength represents an impairing factor not adequately considered by more objective rating methods. If chosen as a method, the caveats detailed on AMA5 p 508 under the heading ‘16.8a Principles’ need to be observed – ie decreased strength cannot be rated in the presence of decreased motion, painful conditions, deformities and absence of parts (eg thumb amputation).

Conditions affecting the shoulder region

2.14 Most shoulder disorders with an abnormal range of movement are assessed according to AMA5 Section 16.4 ‘Evaluating abnormal motion’. (Please note that AMA5 indicates that internal and external rotation of the shoulder are to be measured with the arm abducted in the coronal plane to 90 degrees, and with the elbow flexed to 90 degrees. In those situations where abduction to 90 degrees is not possible, symmetrical measurement of rotation is to be carried out at the point of maximal abduction.)

Rare cases of rotator cuff injury, where the loss of shoulder motion does not reflect the severity of the tear, and there is no associated pain, may be assessed according to AMA5 Section 16.8c ‘Strength evaluation’. Other specific shoulder disorders where the loss of shoulder motion does not reflect the severity of the disorder, associated with pain, should be assessed by comparison with other impairments that have similar effect(s) on upper limb function.

As noted in AMA5 Section 16.7b ‘Arthroplasty’, ‘In the presence of decreased motion, motion impairments are derived separately and combined with the arthroplasty impairment’. This includes those arthroplasties in AMA5 Table 16-27 designated as (isolated).

Please note that in AMA5 Table 16-27 (p 506) the figure for resection arthroplasty of the distal clavicle (isolated) has been changed to 5% upper extremity impairment, and the figure for resection arthroplasty of the proximal clavicle (isolated) has been changed to 8% upper extremity impairment.

Please note that in AMA5 Table 16-18 (p 499) the figures for impairment suggested for the sternoclavicular joint have been changed from 5% upper extremity impairment and 3% whole person impairment, to 25% upper extremity impairment and 15% whole person impairment.

2.15 Ruptured long head of biceps shall be assessed as an upper extremity impairment (UEI) of 3%UEI or 2%WPI where it exists in isolation from other rotator cuff pathology. Impairment for ruptured long head of biceps cannot be combined with any other rotator cuff impairment or with loss of range of movement.

2.16 Diagnosis of impingement is made on the basis of positive findings on appropriate provocative testing and is only to apply where there is no loss of range of motion. Symptoms must have been present for at least 12 months. An impairment rating of 3% UEI or 2% WPI shall apply.

Fractures involving joints

2.17 Displaced fractures involving joint surfaces are generally to be rated by range of motion. If, however, this loss of range is not sufficient to give an impairment rating, and movement is accompanied by pain and there is 2mm or more displacement, allow 2% UEI (1% WPI).

Epicondylitis of the elbow

2.18 This condition is rated as 2% UEI (1% WPI). In order to assess impairment in cases of epicondylitis, symptoms must have been present for at least 18 months. Localised tenderness at the epicondyle must be present and provocative tests must also be positive. If there is an associated loss of range of movement, these figures are not combined, but the method giving the highest rating is used.

Resurfacing procedures

2.19 No additional impairment is to be awarded for resurfacing procedures used in the treatment of localised cartilage lesions and defects in major joints.

Calculating motion impairment

2.20 When calculating impairment for loss of range of movement, it is most important to always compare measurements of the relevant joint(s) in both extremities. If a contralateral ‘normal/uninjured’ joint has less than average mobility, the impairment value(s) corresponding to the uninvolved joint serves as a baseline and is subtracted from the calculated impairment for the involved joint. The rationale for this decision should be explained in the assessor’s report (see AMA5 Section 16.4c, p 543).

Complex regional pain syndrome (upper extremity)

2.21 Complex regional pain syndrome types 1 and 2 should be assessed using the method in Chapter 17 of the Guidelines.

AMA5 Chapter 17 (p 523) applies to the assessment of permanent impairment of the lower extremities, subject to the modifications set out below. Before undertaking an impairment assessment, users of the Guidelines must be familiar with:

- the Introduction in the Guidelines

- chapters 1 and 2 of AMA5

- the appropriate chapter(s) of the Guidelines for the body system they are assessing

- the appropriate chapter(s) of AMA5 for the body system they are assessing.

The Guidelines take precedence over AMA5.

Introduction

3.1 The lower extremities are discussed in AMA5 Chapter 17 (pp 523–564). This section is complex and provides a number of alternative methods of assessing permanent impairment involving the lower extremity. An organised approach is essential.

The approach to assessment of the lower extremity

3.2 Assessment of the lower extremity involves physical evaluation, which can use a variety of methods. In general, the method should be used that most specifically addresses the impairment present. For example, impairment due to a peripheral nerve injury in the lower extremity should be assessed with reference to that nerve rather than by its effect on gait.

3.3 There are several different forms of evaluation that can be used, as indicated inAMA5 sections 17.2b to 17.2n (pp 528–54). AMA5 Table 17-2 (p 526) indicates which evaluation methods can be combined and which cannot. It may be possible to perform several different evaluations, as long as they are reproducible and meet the conditions specified below and in AMA5. The most specific method of impairment assessment should be used. (Please note that in Table 17-2, the boxes in the fourth row (on muscle strength) and seventh column (on amputation) should be closed boxes [x] rather than open boxes [ ].)

3.4 It is possible to use an algorithm to aid in the assessment of lower extremity impairment (LEI). Use of a worksheet is essential. Table 3.5 at the end of this chapter is such a worksheet and may be used in assessment of permanent impairment of the lower extremity.

3.5 In the assessment process, the evaluation giving the highest impairment rating is selected. That may be a combined impairment in some cases, in accordance with the AMA5 Table 17-2 ‘Guide to the appropriate combination of evaluation methods’, using the Combined Values Chart on pp 604–06 of AMA5.

3.6 When the Combined Values Chart is used, the assessor must ensure that all values combined are in the same category of impairment rating (ie percentage of WPI, percentage of lower extremity impairment, foot impairment percentage, and so on). Regional impairments of the same limb (eg several lower extremity impairments) should be combined before converting to a percentage of whole person impairment (WPI).

3.7 AMA5 Table 17-2 (p 526) AMA5) needs to be referred to frequently to determine which impairments can be combined and which cannot. The assessed impairment of a part or region can never exceed the impairment due to amputation of that part or region. For the lower limb, therefore, the maximum evaluation is 40% WPI, the value for proximal above-knee amputation.

Specific interpretation of AMA5 – the lower extremity

3.8 When true leg length discrepancy is determined clinically (see AMA5 Section 17.2b, p 528), the method used must be indicated (eg tape measure from anterior superior iliac spine to the medial malleolus). Clinical assessment of leg length discrepancy is an acceptable method, but if full-length computerised tomography films are available, they should be used in preference. Such an examination should not be ordered solely for determining leg lengths.

3.9 Note that the figures for lower limb impairment in AMA5 table 17-4 (p 528) are incorrect. The correct figures are shown below.

AMA5 Table 17-4: Impairment due to limb length discrepancy

| Discrepancy (cm) | Whole person (lower extremity) impairment (%) |

|---|---|

| 0-1.9 | 0 |

| 2-2.9 | 3 (8) |

| 3-3.9 | 5 (13) |

| 4-4.9 | 7 (18) |

| 5+ | 8 (19) |

3.10 Assessment of gait derangement is only to be used as a method of last resort. Methods of impairment assessment most fitting the nature of the disorder should always be used in preference. If gait derangement (AMA5 Section 17.2c, p 529) is used, it cannot be combined with any other evaluation in the lower extremity section of AMA5.

3.11 Any walking aid used by the subject must be a permanent requirement and not temporary.

3.12 In the application of AMA5 Table 17-5 (p 529), delete item ‘b’, as the Trendelenburg sign is not sufficiently reliable.

3.13 AMA5 Section 17.2d (p 530) is not applicable if the limb other than that being assessed is abnormal (eg if varicose veins cause swelling, or if there is another injury or condition which has contributed to the disparity in size).

3.14 Note that the figures for lower limb impairment given in AMA5 Table 17-6 (p 530) are incorrect. The correct figures are shown below.

AMA5 Table 17-6: Impairment due to unilateral leg muscle atrophy

| Difference in circumference (cm) | Impairment degree | Whole person (lower extremity) impairment (%) |

|---|---|---|

| a. Thigh: The circumference is measured 10cm above the patella, with the knee fully extended and the muscles relaxed. | ||

| 0-0.9 | None | 0 (0) |

| 1-1.9 | Mild | 2 (6) |

| 2-2.9 | Moderate | 4 (11) |

| 3+ | Severe | 5 (12) |

| Difference in circumference (cm) | Impairment degree | Whole person (lower extremity) impairment (%) |

|---|---|---|

| b. Calf: The maximum circumference on the normal side is compared with the circumference at the same level on the affected side. | ||

| 0-0.9 | None | 0 (0) |

| 1-1.9 | Mild | 2 (6) |

| 2-.29 | Moderate | 4 (11) |

| 3+ | Severe | 5 (12) |

3.15 The Medical Research Council gradings for muscle strength are universally accepted. They are not linear in their application, but ordinal. Only the six grades (0–5) should be used, as they are reproducible among experienced assessors. The descriptions in AMA5 Table 17-7 (p 531) are correct. The results of electrodiagnostic methods and tests are not to be considered in evaluating muscle testing, which can be performed manually. AMA5 Table 17-8 (p 532) is to be used for this method of evaluation.

3.16 Although range of motion (ROM) appears to be a suitable method for evaluating impairment (see AMA5 Section 17.2f, pp 533–38), it may be subject to variation because of pain during motion at different times of examination, possible lack of cooperation by the person being assessed and inconsistency. If there is such inconsistency, then ROM cannot be used as a valid parameter of impairment evaluation.

AMA5 Table 17-10 (p 537) is misleading as it has valgus and varus deformity in the same table as restriction of movement, possibly suggesting that these impairments may be combined. This is not the case. Any valgus/ varus deformity present which is due to the underlying lateral or medial compartment arthritis, cannot be combined with loss of range of movement. Therefore, when faced with an assessment in which there is a rateable loss of range of movement as well as a rateable deformity, calculate both impairments and use the greater. Valgus and varus knee angulation are to be measured in a weight-bearing position using a goniometer. It is important to bear in mind that valgus and/or varus alignments of the knee may be constitutional. It is also important to always compare with the opposite knee.

3.17 If range of motion is used as an assessment measure, then AMA5 Tables 17-9 to 17 14 (p 537) are selected for the joint or joints being tested. If a joint has more than one plane of motion, the impairment assessments for the different planes should be added. For example, any impairment of the six principal directions of motion of the hip joint are added (see AMA5, p 533).

In AMA5 Table 17-10 (p 537), on knee impairment, the sentence should read: ‘Deformity measured by femoral-tibial angle; 3° to 9° valgus is considered normal’.

In AMA5 Table 17-11 (ankle motion) the range for mild flexion contracture should be one to 10°, for moderate flexion contracture it should be 11° to 19°, and for severe flexion contracture it should be 20° plus.

The revised Table 17-11 is below.

AMA5 Table 17-11: Ankle motion impairment estimates

| Whole person (lower extremity) [foot] impairment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion | Mild 3% (7%) [10%] | Moderate 6% (15%) [21%] | Severe 12% (30%) [43%] |

| Plantar flexion capability | 11°-20° | 1°-10° | None |

| Flexion contracture | 1°-10° | 11°-19° | 20°+ |

| Extension | 10°-0° (neutral) | - | - |

When calculating impairment for loss of range of movement, it is most important to always compare measurements of the relevant joint(s) in both extremities. If a contralateral ‘normal/uninjured’ joint has less than average mobility, the impairment value(s) corresponding to the uninvolved joint serves as a baseline, and is subtracted from the calculated impairment for the involved joint. The rationale for this decision should be explained in the assessor’s report (see AMA5 Section 16.4c, p 454).

3.18 Ankylosis is to be regarded as the equivalent to arthrodesis in impairment terms only. For the assessment of impairment, when a joint is ankylosed (AMA5 section 17.2g, pp 538-543), the calculation to be applied is to select the impairment if the joint is ankylosed in optimum position (see table 3.1 below), and then if not ankylosed in the optimum position, by adding (not combining) the values of percentage of WPI using tables 17-15 to 17-30 (pp 538-543 AMA5).

Table 3.1: Impairment for ankylosis in the optimum position

| Joint | Whole person % | Lower extremity % | Ankle or foot % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hip | 20 | 50 | - |

| Knee | 27 | 67 | - |

| Pantalar | 19 | 47 | 67 |

| Ankle | 15 | 37 | 53 |

| Triple | 6 | 15 | 21 |

| Subtalar | 4 | 10 | 14 |

Note that the figures in Table 3.1 suggested for ankle impairment are greater than those suggested in AMA5.

Ankylosis of the ankle in the neutral/optimal position equates with 15 (37) [53]% impairment as per Table 3.1. Table 3.1(a) is provided below as a guide to evaluate additional impairment owing to variation from the neutral position. The additional amounts at the top of each column are added to the figure for impairment in the neutral position. In keeping with the value given on page 541 of AMA5, the maximum impairment for ankylosis of the ankle remains at 25 (62) [88]% impairment.

Table 3.1(a): Impairment for ankylosis in variation from the optimum position

| Whole person (lower extremity) [foot] impairment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | 2 (5) [7]% | 4 (10) [14]% | 7 (17) [24]% | 10 (25) [35]% |

| Dorsiflexion | 5°-9° | 10°-19° | 20°-29° | 30°+ |

| Plantar flexion | - | 10°-19° | 20°-29° | 30°+ |

| Varus | 5°-9° | 10°-19° | 20°-29° | 30°+ |

| Valgus | - | 10°-19° | 20°-29° | 30°+ |

| Internal rotation | 0°-9° | 10°-19° | 20°-29° | 30°+ |

| External rotation | 15°-19° | 20°-29° | 30°-39° | 40°+ |

3.19 Impairment due to arthritis (AMA5 Section 17.2n, pp 544–45) following a work-related injury is uncommon, but may occur in isolated cases. The presence of arthritis may indicate a pre-existing condition and this should be assessed and an appropriate deduction made (see Chapter 1).

3.20 The presence of osteoarthritis is defined as cartilage loss. Cartilage loss can be measured by properly aligned plain X-ray, or by direct vision (arthroscopy), but impairment can only be assessed according to the radiologically determined cartilage loss intervals shown in AMA5 Table 17-31 (p 544). When assessing impairment of the knee joint, which has three compartments, only the compartment with the major impairment is used in the assessment. That is, measured impairments in the different compartments cannot be added or combined.

3.21 Detecting the subtle changes of cartilage loss on plain radiography requires comparison with the normal side. All joints should be imaged directly through the joint space, with no overlapping of bones. If comparison views are not available, AMA5 Table 17-31 (p 544) is used as a guide to assess joint space narrowing.

3.22 One should be cautious in making a diagnosis of cartilage loss on plain radiography if secondary features of osteoarthritis, such as osteophytes, subarticular cysts or subchondral sclerosis are lacking, unless the other side is available for comparison. The presence of an intra-articular fracture with a step in the articular margin in the weight-bearing area implies cartilage loss.

3.23 The accurate radiographic assessment of joints always requires at least two views. In some cases, further supplementary views will optimise the detection of joint space narrowing or the secondary signs of osteoarthritis.

Sacro-iliac joint: Being a complex joint, modest alterations are not detected on radiographs, and cross sectional imaging may be required. Radiographic manifestations accompany pathological alterations. The joint space measures between 2mm and 5mm. Osteophyte formation is a prominent characteristic of osteoarthritis of the sacro-iliac joint.

Hip: An anteroposterior view of the pelvis and a lateral view of the affected hip are ideal. If the affected hip joint space is narrower than the asymptomatic side, cartilage loss is regarded as being present. If the anteroposterior view of the pelvis has been obtained with the patient supine, it is important to compare the medial joint space of each hip, as well as superior joint space, as this may be the only site of apparent change. If both sides are symmetrical, then other features, such as osteophytes, subarticular cyst formation, and calcar thickening, should be taken into account to make a diagnosis of osteoarthritis.

Knee – Tibio-femoral joint: The best view for assessment of cartilage loss in the knee is usually the erect intercondylar projection, as this profiles and stresses the major weight-bearing area of the joint, which lies posterior to the centre of the long axis. The ideal X-ray is a posteroanterior view, with the patient standing, knees slightly flexed, and the X-ray beam angled parallel to the tibial plateau (Rosenberg view). Both knees can be readily assessed with the one exposure. It should be recognised that joint space narrowing in the knee does not necessarily equate with articular cartilage loss, as deficiency or displacement of the menisci can also have this effect. Secondary features, such as subchondral bone change and past surgical history, must also be taken into account.

Knee – Patello-femoral joint: This should be assessed in the ‘skyline’ view, again preferably with the other side for comparison. The X-ray should be taken with 30 degrees of knee flexion to ensure that the patella is load-bearing and has engaged the articular surface femoral groove.

- Footnote to AMA5 Table 17-31 (p 544) regarding patello-femoral pain and crepitation:

- This item is only to be used if there is a history of direct injury to the front of the knee, or in cases of patellar translocation/dislocation without direct anterior trauma. This item cannot be used as an additional impairment when assessing arthritis of the knee joint itself, of which it forms a component. If patello-femoral crepitus occurs in isolation (ie with no other signs of arthritis) following either of the above, then it can be combined with other diagnosis-based estimates (AMA5 Table 17-33, p 546). Signs of crepitus need to be present at least one year post-injury.

- Note: Osteoarthritis of the patello-femoral joint cannot be used as an additional impairment when assessing arthritis of the knee joint itself, of which it forms a component.

Ankle: The ankle should be assessed in the mortice view (preferably weight-bearing), with comparison views of the other side, although this is not as necessary as with the hip and knee.

Subtalar: This joint is better assessed by CT (in the coronal plane) than by plain radiography. The complex nature of the joint does not lend itself to accurate and easy plain X-ray assessment of osteoarthritis.

Talonavicular and calcaneocuboid: Anteroposterior and lateral views are necessary. Osteophytes may assist in making the diagnosis.

Intercuneiform and other intertarsal joints: Joint space narrowing may be difficult to assess on plain radiography. CT (in the axial plane) may be required. Associated osteophytes and subarticular cysts are useful adjuncts to making the diagnosis of osteoarthritis in these small joints.

Great toe metatarsophalangeal: Anteroposterior and lateral views are required. Comparison with the other side may be necessary. Secondary signs may be useful.

Interphalangeal: It is difficult to assess small joints without taking secondary signs into account. The plantar-dorsal view may be required to get through the joints, in a foot with flexed toes.

3.24 If arthritis is used as the basis for assessing impairment, then the rating cannot be combined with gait disturbance, muscle atrophy, muscle strength or range of movement assessments. It can be combined with a diagnosis-based estimate (AMA5 Table 17-2, p 526).

3.25 Where there has been amputation of part of a lower extremity Table 17-32 (p 545, AMA5) applies. In that table, the references to three inches for below the knee amputation should be converted to 7.5cm.

3.26 AMA5 Section 17.2j (pp 545–49) lists a number of conditions that fit a category of diagnosis-based estimates. They are listed in AMA5 Tables 17-33, 17-34 and 17-35 (pp 546–49). When using this table it is essential to read the footnotes carefully. The category of mild cruciate and collateral ligament laxity has inadvertently been omitted in Table 17-33. The appropriate rating is 5 (12)% whole person (lower extremity) impairment.

3.27 It is possible to combine impairments from Tables 17-33, 17-34 and 17-35 for diagnosis-related estimates with other components (eg nerve injury) using the Combined Values Chart (AMA5, pp 604–06) after first referring to the Guidelines for the appropriate combination of evaluation methods (see Table 3.5).

3.28 Pelvic fractures: Pelvic fractures are to be assessed as per Table 4.3 in Chapter 4 the Guidelines, and not as per AMA5 Table 17-33 (p 546).

Hip: The item in relation to femoral neck fracture ‘malunion’ is not to be used in assessing impairment. Use other available methods.

Femoral osteotomy:

- Good result: 10 (25)

- Poor result: Estimate according to examination and arthritic degeneration

Tibial plateau fractures: Table 3.2 of the Guidelines (below), replaces the instructions for tibial plateau fractures in AMA5 Table 17-33 (p 546).

Table 3.2: Impairment for tibial plateau fractures

In deciding whether the fracture falls into the mild, moderate or severe categories, the assessor must take into account:

- the extent of involvement of the weight-bearing area of the tibial plateau

- the amount of displacement of the fracture(s)

- the amount of comminution present.

| Grade | Whole person (lower extremity) impairment (%) |

|---|---|

| Undisplaced | 2 (5) |

| Mild | 5 (12) |

| Moderate | 10 (25) |

| Severe | 15 (37) |

Patello-femoral joint replacement: Assess the knee impairment in the usual way and combine with 9% WPI (22% LEI) for isolated patello-femoral joint replacement.

Total ankle replacement:

Table 3.3: Rating for ankle replacement results

The points system for rating total ankle replacements is to be the same as for total hip and total knee replacements, with the following impairment ratings:

| Result | WPI (LEI) % |

|---|---|

| Good result: 85–100 points: | 12 (30) |

| Fair result: 50–84 points: | 16 (40) |

| Poor result: <50 points: | 20 (50) |

| Number of points | ||

|---|---|---|

| a. Pain | ||

| None | 50 | |

| Slight | ||

| Stairs only | 40 | |

| Walking and stairs | 30 | |

| Moderate | ||

| Occasional | 20 | |

| Continual | 10 | |

| Severe | 0 | |

| b. Range of motion | ||

| i. Flexion | ||

| > 20° | 15 | |

| 11° - 20° | 10 | |

| 5° - 10° | 5 | |

| < 5° | 0 | |

| ii. Extension: | ||

| > 10° | 10 | |

| 5° - 10° | 5 | |

| < 5° | 0 | |

| c. Range of motion | ||

| i. Limp | ||

| None | 10 | |

| Slight | 7 | |

| Moderate | 4 | |

| Severe | 0 | |

| ii. Supportive device | ||

| None | 5 | |

| Cane | 3 | |

| One crutch | 1 | |

| Two crutches | 0 | |

| iii. Distance walked | ||

| Unlimited | 5 | |

| Six blocks | 4 | |

| Three blocks | 3 | |

| Indoors | 2 | |

| Bed or chair | 0 | |

| iv. Stairs | ||

| Normal | 5 | |

| Using rail | 4 | |

| One at a time | 2 | |

| Unable to climb | 0 | |

| Sub-total: | ||

| Deductions (minus) d and e | Number of points |

|---|---|

| d. Varus | |

| < 5° | 0 |

| 5° - 10° | 10 |

| > 10° | 15 |

| e. Valgus | |

| < 5° | 0 |

| 5° - 10° | 10 |

| > 10° | 15 |

| Sub-total: | |

Tibia-os calcis angle: The table given below for the impairment of loss of the tibia-os calcis angle is to replace AMA5 Table 17-29 (p 542) and the section in AMA5 Table 17-3 (p 546) dealing with loss of tibia-os calcis angle. These two sections are contradictory, and neither gives a full range of loss of angle.

Table 3.4 Impairment for loss of the tibia-os calcis angle

| Angle (degree) | Whole person (lower extremity) [foot] impairment (%) |

|---|---|

| 110-100 | 5 (12) [17] |

| 99-90 | 8 (20) [28] |

| <90 | +1 (2) [3] per degree, up to 15 (37) [54] |

Hindfoot intra-articular fractures: In the interpretation of AMA5 Table 17-33 (p 547, AMA5), reference to the hindfoot, intra-articular fractures, the words subtalar bone, talonavicular bone, and calcaneocuboid bone imply that the bone is displaced on one or both sides of the joint mentioned. To avoid the risk of double assessment, if avascular necrosis with collapse is used as the basis of impairment assessment, it cannot be combined with the relevant intra-articular fracture in Table 17-33, column 2. In Table 17-33, column 2, metatarsal fracture with loss of weight transfer means dorsal displacement of the metatarsal head.

Plantar fasciitis: If there are persistent symptoms and clinical findings after 18 months, this is rated as 2% LEI (1% WPI).

Resurfacing procedures: No additional impairment is to be awarded for resurfacing procedures used in the treatment of localised cartilage lesions and defects in major joints.

3.29 AMA5 tables 17-34 and 17-35 (pp 548–49) use a different concept of evaluation. A point score system is applied, and then the total points calculated for the hip (or knee) joint are converted to an impairment rating from Table 17-33. Tables 17-34 and 17-35 refer to hip and knee joint replacements respectively. Note that, while all the points are added in Table 17-34, some points are deducted when Table 17-35 is used. (Note that hemiarthroplasty rates the same as total joint replacement.)

3.30 In respect of ‘distance walked’ under ‘b. Function’ in AMA5 Table 17-34 (p 548), the distance of six blocks should be construed as 600 metres, and three blocks as 300 metres.

Note that AMA5 Table 17-35 (p 549) is incorrect. The correct table is shown below:

AMA5 Table 17-35: Rating knee replacement results

| Number of points | ||

|---|---|---|

| a. Pain | ||

| None | 50 | |

| Mild or occasional | 45 | |

| Stairs only | 40 | |

| Walking and stairs | 30 | |

| Moderate | ||

| Occasional | 20 | |

| Continual | 10 | |

| Severe | 0 | |

| b. Range of motion | ||

| Add 1 point per 5° up to 125° | 25 (maximum) | |

| c. Stability (maximum movement in any position) | ||

| Anterioposterior | ||

| < 5mm | 10 | |

| 5 - 9mm | 5 | |

| > 9mm | 0 | |

| Mediolateral | ||

| 5° | 15 | |

| 6° - 9° | 10 | |

| 10° - 14° | 5 | |

| > 14° | 0 | |

| Sub-total: | ||

| Deductions (minus) d, e, f | Number of points |

|---|---|

| d. Flexion contracture | |

| 5° - 9° | 2 |

| 10° - 15° | 5 |

| 16° - 20° | 10 |

| > 20° | 20 |

| e. Extension lag | |

| < 10° | 5 |

| 10° - 20° | 10 |

| > 20° | 15 |

| f. Tibio-femoral alignment* | |

| > 15° valgus | 20 |

| 11° - 15° valgus | 3 points per degree |

| 5° - 10° valgus | 0 |

| 0° - 4° valgus | 3 points per degree |

| Any varus | 20 |

| Deductions sub-total: | |

* Refer to the unaffected limb to take into account any constitutional variation.

3.32 When assessing the impairment due to peripheral nerve injury (AMA5, pp 550–52) assessors should read the text in this section. Note that separate impairments for the motor, sensory and dysaesthetic components of nerve dysfunction in AMA5 Table 17-37 (p 552) are to be combined.

3.33 Note that the (posterior) tibial nerve is not included in Table 17-37, but its contribution can be calculated by subtracting ratings of common peroneal nerves from sciatic nerve ratings.

3.34 Peripheral nerve injury impairments can be combined with other impairments, but not those for gait derangement, muscle atrophy, muscle strength or complex regional pain syndrome, as shown in AMA5 Table 17-2 (p 526). Motor and sensory impairments given in Table 17-37 are for complete loss of function and assessors must still use Table 16-10 and 16-11 in association with Table 17-37.

3.35 Complex regional pain syndrome types 1 and 2 are to be assessed using the method in Chapter 17 of the Guidelines.

3.36 Lower extremity impairment due to vascular disorders (AMA5, pp 553–54) is evaluated using AMA5 Table 17-38 (p 554). Note that Table 17-38 gives values for lower extremity impairment, not WPI. In that table, there is a range of lower extremity impairments within each of the classes 1 to 5. As there is a clinical description of which conditions place a person’s lower extremity in a particular class, the assessor has a choice of impairment rating within a class, the value of which is left to the clinical judgement of the assessor.

3.37 When measuring dorsiflexion at the ankle, the test is carried out initially with the knee in extension and then repeated with the knee flexed to 45 degrees. The average of the maximum angles represents the dorsiflexion range of motion (AMA5 Figure 17-5, p 535).

Table 3.5: Lower extremity worksheet

| Item | Impairment | AMA5 table | AMA5 page | Potential impairment | Selected impairment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Limb length discrepancy | 17-4 | 528 | ||

| 2 | Gait derangement | 17-5 | 529 | ||

| 3 | Unilateral muscle atrophy | 17-6 | 530 | ||

| 4 | Muscle weakness | 17-8 | 532 | ||

| 5 | Range of motion | 17-9 to 17-14 | 537 | ||

| 6 | Joint ankylosis | 17-15 to 17-30 | 538-543 | ||

| 7 | Arthritis | 17-31 | 544 | ||

| 8 | Amputation | 17-32 | 545 | ||

| 9 | Diagnosis-based estimates | 17-33 to 17-35 | 546-549 | ||

| 10 | Skin loss | 17-36 | 550 | ||

| 11 | Peripheral nerve deficit | 17-37 | 552 | ||

| 12 | Complex regional pain syndrome | Section 16.5e | 495-497 | ||

| 13 | Vascular disorder | 17-38 | 554 | ||

| Combined impairment rating (refer to AMA5 Table 17-2, p526 for permissible combinations) | |||||

Potential impairment is the impairment percentage for that method of assessment. Selected impairment is the impairment, or impairments selected, that can be legitimately combined with other lower extremity impairments to give a final lower extremity impairment rating.

AMA5 Chapter 15 (p 373) applies to the assessment of permanent impairment of the spine, subject to the modifications set out below. Before undertaking an impairment assessment, users of the Guidelines must be familiar with:

- the Introduction in the Guidelines

- chapters 1 and 2 of AMA5

- the appropriate chapter(s) of the Guidelines for the body system they are assessing.

- the appropriate chapter(s) of AMA5 for the body system they are assessing.

- The Guidelines take precedence over AMA5.

Introduction

4.1 The spine is discussed in Chapter 15 of AMA5 (pp 373–431). That chapter presents two methods of assessment, the diagnosis-related estimates method and the range of motion method. Evaluation of impairment of the spine is only to be done using diagnosis-related estimates (DREs).

4.2 The DRE method relies especially on evidence of neurological deficits and less common, adverse structural changes, such as fractures and dislocations. Using this method, DREs are differentiated according to clinical findings that can be verified by standard medical procedures.

4.3 The assessment of spinal impairment is made when the person’s condition has stabilised and has reached maximum medical improvement. This is considered to occur when the worker’s condition is well stabilised and unlikely to change substantially in the next year, with or without medical treatment. If surgery has been performed, the outcome of the surgery as well as structural inclusions must be taken into consideration when making the assessment.

Assessment of the spine

4.4 The assessment should include a comprehensive, accurate history, a review of all pertinent records available at the assessment, a comprehensive description of the individual’s current symptoms and their relationship to activities of daily living (ADL); a careful and thorough physical examination; and all findings of relevant laboratory, imaging, diagnostic and ancillary tests available at the assessment. Imaging findings that are used to support the impairment rating should be concordant with symptoms and findings on examination. The assessor should record whether diagnostic tests and radiographs were seen or whether they relied solely on reports.

4.5 The DRE model for assessment of spinal impairment should be used. The range of motion model (AMA5 sections 15.8–15.13 inclusive, pp 398–427) should not be used.

4.6 If a person has spinal cord or cauda equina damage, including bowel, bladder and/or sexual dysfunction, he or she is assessed according to the method described in AMA5 Section 15.7 and AMA5 Table 15.6 (a)–(g) (pp 395–98).

4.7 If an assessor is unable to distinguish between two DRE categories, then the higher of those two categories should apply. The reasons for the inability to differentiate should be noted in the assessor’s report.

4.8 Possible influence of future treatment should not form part of the impairment assessment. The assessment should be made on the basis of the person’s status at the time of interview and examination, if the assessor is convinced that the condition is stable and permanent. Likewise, the possibility of subsequent deterioration, as a consequence of the underlying condition, should not be factored into the impairment evaluation. Commentary can be made regarding the possible influence, potential or requirements for further treatment, but this does not affect the assessment of the individual at the time of impairment evaluation.

4.9 All spinal impairments are to be expressed as a percentage of WPI.

4.10 AMA5 Section 15.1a (pp 374–77) is a valuable summary of history and physical examination, and should be thoroughly familiar to all assessors.

4.11 The assessor should include in the report a description of how the impairment rating was calculated, with reference to the relevant tables and figures used.

4.12 The optimal method to measure the percentage compression of a vertebral body is a well-centred plain X-ray. Assessors should state the method they have used. The loss of vertebral height should be measured at the most compressed part and must be documented in the impairment evaluation report. The estimated normal height of the compressed vertebra should be determined, where possible, by averaging the heights of the two adjacent (unaffected and normal) vertebrae.

Specific interpretation of AMA5

4.13 The range-of-motion (ROM) method is not used, hence any reference to this is omitted (includingAMA5 Table 15-7, p 404).

4.14 Motion segment integrity alteration can be either increased translational or angular motion, or decreased motion resulting from developmental changes, fusion, fracture healing, healed infection or surgical arthrodesis. Motion of the individual spine segments cannot be determined by a physical examination, but is evaluated with flexion and extension radiography.

4.15 The assessment of altered motion segment integrity is to be based upon a report of trauma resulting in an injury, and not on developmental or degenerative changes.

4.16 When routine imaging is normal and severe trauma is absent, motion segment disturbance is rare. Thus, flexion and extension imaging is indicated only when a history of trauma or other imaging leads the physician to suspect alteration of motion segment integrity.

DRE definitions of clinical findings

4.17 The preferred method for recording ROM is as a fraction or percentage of the range or loss of the range. For example, either ‘cervical movement was one half (or 50%) of the normal range of motion’ or ‘there was a loss of one half (or 50%) of the normal range of movement of the cervical spine’.

4.18 DRE II is a clinical diagnosis based upon the features of the history of the injury and clinical features. Clinical features which are consistent with DRE II and which are present at the time of assessment include radicular symptoms in the absence of clinical signs (that is, non-verifiable radicular complaints), muscle guarding or spasm, or asymmetric loss of range of movement. Localised (not generalised) tenderness may be present. In the lumbar spine, additional features include a reversal of the lumbosacral rhythm when straightening from the flexed position and compensatory movement for an immobile spine, such as flexion from the hips. In assigning category DRE II, the assessor must provide detailed reasons why the category was chosen.

4.19 Asymmetric or non-uniform loss of ROM may be present in any of the three planes of spinal movement. Asymmetry during motion caused by muscle guarding or spasm is included in the definition.

Asymmetric loss of ROM may be present for flexion and extension. For example, if cervical flexion is half the normal range (loss of half the normal range) and cervical extension is one-third of the normal range (loss of two thirds of the range), asymmetric loss of ROM may be considered to be present.

4.20 While imaging and other studies may assist medical assessors in making a diagnosis, the presence of a morphological variation from ‘normal’ in an imaging study does not confirm the diagnosis. To be of diagnostic value, imaging studies must be concordant with clinical symptoms and signs. In other words, an imaging test is useful to confirm a diagnosis, but an imaging study alone is insufficient to qualify for a DRE category (excepting spinal fractures).

4.21 The clinical findings used to place an individual in a DRE category are described in AMA5 Box 15-1 (pp 382–83).

The reference to ‘electro-diagnostic verification of radiculopathy’ should be disregarded.

(The use of electro-diagnostic procedures such as electromyography is proscribed as an assessment aid for decisions about the category of impairment into which a person should be placed. It is considered that competent assessors can make decisions about which DRE category a person should be placed in from the clinical features alone. The use of electro-diagnostic differentiators is generally unnecessary).

4.22 The cauda equina syndrome is defined in Box 15.1 in Chapter 15 of AMA5 (p 383) as ‘manifested by bowel or bladder dysfunction, saddle anaesthesia and variable loss of motor and sensory function in the lower limbs’. For a cauda equina syndrome to be present there must be bilateral neurological signs in the lower limbs and sacral region. Additionally, there must be a radiological study which demonstrates a lesion in the spinal canal, causing a mass effect on the cauda equina with compression of multiple nerve roots. The mass effect would be expected to be large and significant. A lumbar MRI scan is the diagnostic investigation of choice for this condition. A cauda equina syndrome may occasionally complicate lumbar spine surgery when a mass lesion will not be present in the spinal canal on radiological examination.

4.23 The cauda equina syndrome and neurogenic bladder disorder are to be assessed by the method prescribed in the spine chapter of AMA5 Section 15.7 (pp 395–98). For an assessment of neurological impairment of bowel or bladder, there must be objective evidence of spinal cord or cauda equina injury.

Applying the DRE method

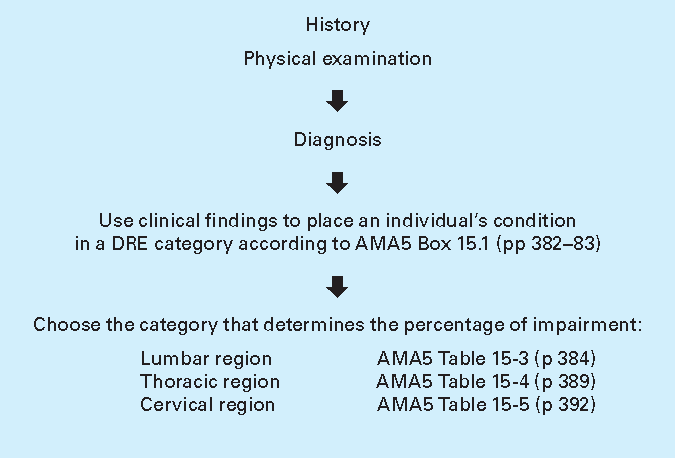

4.24 The specific procedures and directions section of AMA5 Section 15.2a (pp 380–81) indicates the steps that should be followed to evaluate impairment of the spine (excluding references to the ROM method). Table 4.1 below is a simplified version of that section, incorporating the amendments listed above.

4.25 Common developmental findings, spondylosis, spondylolisthesis and disc protrusions without radiculopathy occur in 7%, 3% and up to 30% of cases involving individuals up to the age of 40 respectively (AMA5, p 383). Their presence does not of itself mean that the individual has an impairment due to injury.

4.26 Loss of sexual function should only be assessed where there is other objective evidence of spinal cord, cauda equina or bilateral nerve root dysfunction. The ratings are described in AMA5 Table 15-6 (pp 396–97). There is no additional impairment rating system for loss of sexual function in the absence of objective neurological findings. Loss of sexual function is not assessed as an ADL.

4.27 Radiculopathy is the impairment caused by malfunction of a spinal nerve root or nerve roots. In general, in order to conclude that radiculopathy is present, two or more of the following criteria should be found, one of which must be major (major criteria in bold):

- loss or asymmetry of reflexes

- muscle weakness that is anatomically localised to an appropriate spinal nerve root distribution

- reproducible impairment of sensation that is anatomically localised to an appropriate spinal nerve root distribution

- positive nerve root tension (AMA5 Box 15-1, p 382)

- muscle wasting – atrophy (AMA5 Box 15-1, p 382)

- findings on an imaging study consistent with the clinical signs (AMA5, p 382).

4.28 Radicular complaints of pain or sensory features that follow anatomical pathways but cannot be verified by neurological findings (somatic pain, non-verifiable radicular pain) do not alone constitute radiculopathy.

4.29 Global weakness of a limb related to pain or inhibition or other factors does not constitute weakness due to spinal nerve malfunction.

4.30 Vertebral body fractures and/or dislocations at more than one vertebral level are to be assessed as follows:

- Measure the percentage loss of vertebral height at the most compressed part for each vertebra, then

- Add the percentage loss at each level:

- total loss of more than 50% = DRE IV

- total loss of 25% to 50% = DRE III

- total loss of less than 25% = DRE II

- If radiculopathy is present then the person is assigned one DRE category higher.

One or more end plate fractures in a single spinal region without measurable compression of the vertebral body are assessed as DRE category II.

Posterior element fractures (excludes fractures of transverse processes and spinous processes) at multiple levels are assessed as DRE Ill.

4.31 Displaced fractures of transverse or spinous processes at one or more levels are assessed as DRE category II because the fracture does not disrupt the spinal canal (AMA5, p 385) and do not cause multilevel structural compromise.

4.32 Within a spinal region, separate spinal impairments are not combined. The highest-value impairment within the region is chosen. Impairments in different spinal regions are combined using the combined values chart (AMA5, pp 604-06).