Print PDF

Motor accident permanent impairment guidelines

Effective from 1 June 2018, these Guidelines are for insurers, health practitioners and lawyers who are helping patients or clients injured in motor vehicle accidents that occurred between 5 October 1999 and 30 November 2017.

You can also download the PDF version of this document.

General introduction

These Motor Accident Permanent Impairment Guidelines (these Guidelines) are issued by State Insurance Regulatory Authority (SIRA). They apply to motor accidents occurring between 5 October 1999 and 30 November 2017 (inclusive), and are Motor Accidents Medical Guidelines issued under section 44(1)(c) of the Motor Accidents Compensation Act 1999 (the MAC Act).

These Guidelines replace the Permanent Impairment Guidelines – Guidelines for the assessment of permanent impairment of a person injured as a result of a motor vehicle accident, issued by the Motor Accidents Authority and published in the NSW Government Gazette number 90 of 13 July 2007 at page 4581.

Under the MAC Act, damages for non-economic loss can only be awarded where the permanent impairment is greater than 10% and is the result of an injury caused by a motor accident. The assessment of the degree of permanent impairment of an injured person is to be made in accordance with these Guidelines.

These Guidelines are based on the American Medical Association’s Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, Fourth Edition (third printing, 1995) (AMA4 Guides). The AMA4 Guides are widely used as an authoritative source for the assessment of permanent impairment, however these Guidelines make significant changes to the AMA4 Guides to align them with Australian clinical practice and to better suit the purposes of the MAC Act.

These Guidelines commence on 1 June 2018.

Introduction

1.1 These Motor Accident Permanent Impairment Guidelines have been developed for the purpose of assessing the degree of permanent impairment arising from the injury caused by a motor accident, in accordance with Section 133(2)(a) of the Motor Accidents Compensation Act 1999 (NSW) (the Act).

1.2 These Guidelines are based on the American Medical Association’s Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, Fourth Edition (third printing, 1995) (AMA4 Guides). However, there are some very significant departures from that document in these Guidelines. A medical assessor undertaking impairment assessments for the purposes of the Act must read these Guidelines in conjunction with the AMA4 Guides. These Guidelines are definitive with regard to the matters they address. Where they are silent on an issue, the AMA4 Guides should be followed. In particular, chapters 1 and 2 of the AMA4 Guides should be read carefully in conjunction with clauses 1.1 to 1.46 of these Guidelines. Some of the examples in the AMA4 Guides are not valid for the assessment of impairment under the Act. It may be helpful for medical assessors to mark their working copy of the AMA4 Guides with the changes required by these Guidelines.

Application of these Guidelines

1.3 These Guidelines apply under the Act to the assessment of the degree of permanent impairment that has resulted from an injury caused by a motor accident occurring between 5 October 1999 and 30 November 2017 (inclusive).

1.4 For accidents that occurred on or after 1 December 2017, ‘Part 6 of the Motor Accident Guidelines: Permanent impairment’ apply, as published by the State Insurance Regulatory Authority (the Authority).

Causation of injury

1.5 An assessment of the degree of permanent impairment is a medical assessment matter under clause 2(a) of Schedule 2 of the Act. The assessment must determine the degree of permanent impairment of the injured person as a result of the injury caused by the motor accident. A determination as to whether the injured person’s impairment is related to the accident in question is therefore implied in all such assessments. Medical assessors must be aware of the relevant provisions of the AMA4 Guides, as well as the common law principles that would be applied by a court (or claims assessor) in considering such issues.

1.6 Causation is defined in the Glossary at page 316 of the AMA4 Guides as follows:

‘Causation means that a physical, chemical or biologic factor contributed to the occurrence of a medical condition. To decide that a factor alleged to have caused or contributed to the occurrence or worsening of a medical condition has, in fact, done so, it is necessary to verify both of the following:

1. The alleged factor could have caused or contributed to worsening of the impairment, which is a medical determination.

2. The alleged factor did cause or contribute to worsening of the impairment, which is a non-medical determination.’

This, therefore, involves a medical decision and a non-medical informed judgement.

1.7 There is no simple common test of causation that is applicable to all cases, but the accepted approach involves determining whether the injury (and the associated impairment) was caused or materially contributed to by the motor accident. The motor accident does not have to be a sole cause as long as it is a contributing cause, which is more than negligible. Considering the question ‘Would this injury (or impairment) have occurred if not for the accident?’ may be useful in some cases, although this is not a definitive test and may be inapplicable in circumstances where there are multiple contributing causes.

Impairment and disability

1.8 It is critically important to clearly define the term impairment and distinguish it from the disability that may result.

1.9 Impairment is defined as an alteration to a person’s health status. It is a deviation from normality in a body part or organ system and its functioning. Hence, impairment is a medical issue and is assessed by medical means.

1.10 This definition is consistent with that of the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities & Handicaps, Geneva 1980, which has defined impairment as ‘any loss or abnormality of psychological, physiological or anatomical structure or function’.

1.11 Disability, on the other hand, is a consequence of an impairment. The WHO definition is ‘any restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being’.

1.12 Confusion between the two terms can arise because in some instances the clearest way to measure an impairment is by considering the effect on a person’s activities of daily living (that is, on the consequent disability). The AMA4 Guides, in several places, refer to restrictions in the activities of daily living of a person. Hence the disability is being used as an indicator of severity of impairment.

1.13 Where alteration in activities of daily living forms part of the impairment evaluation, for example when assessing brain injury or scarring, refer to the ‘Table of activities of daily living’ on page 317 of the AMA4 Guides. The medical assessor should explain how the injury impacts on activities of daily living in the impairment evaluation report.

1.14 Two examples may help emphasise the distinction between impairment and disability:

1.14.1 The loss of the little finger of the right hand would be an equal impairment for both a bank manager and a concert pianist and so, for these Guidelines, the impairment is identical. But the concert pianist has sustained a greater disability.

1.14.2 An upper arm injury might make it impossible for an injured person to contract the fingers of the right hand. That loss of function is an impairment. However, the consequences of that impairment, such as an inability to hold a cup of coffee or button up clothes, constitute a disability.

1.15 A handicap is a further possible consequence of an impairment or disability, being a disadvantage that limits or prevents fulfilment of a role that is/was normal for that individual. The concert pianist in the example above is likely to be handicapped by their impairment.

1.16 It must be emphasised, in the context of these Guidelines, that it is not the role of the medical assessor to determine disability, other than as described in clause 1.12 (above).

Evaluation of impairment

1.17 The medical assessor must evaluate the available evidence and be satisfied that any impairment:

1.17.1 is an impairment arising from an injury caused by the accident, and

1.17.2 is an impairment as defined in clause 1.9 (above).

1.18 An assessment of the degree of permanent impairment involves three stages:

- medical evidence (doctors’, hospitals’ and other health practitioners’ notes, records and reports)

- medico-legal reports

- diagnostic findings

- other relevant evidence

1.18.1 a review and evaluation of all the available evidence including:

1.18.2 an interview and a clinical examination, wherever possible, to obtain the information specified in these Guidelines and the AMA4 Guides necessary to determine the percentage impairment, and

1.18.3 the preparation of a certificate using the methods specified in these Guidelines that determines the percentage of permanent impairment, including the calculations and reasoning on which the determination is based. The applicable parts of these Guidelines and the AMA4 Guides should be referenced.

Permanent impairment

1.19 Before an evaluation of permanent impairment is undertaken, it must be shown that the impairment has been present for a period of time, and is static, well stabilised and unlikely to change substantially regardless of treatment. The AMA4 Guides (page 315) state that permanent impairment is impairment that has become static or well stabilised with or without medical treatment and is not likely to remit despite medical treatment. A permanent impairment is considered to be unlikely to change substantially (i.e. by more than 3% whole person impairment (WPI) in the next year with or without medical treatment. If an impairment is not permanent, it is inappropriate to characterise it as such and evaluate it according to these Guidelines.

1.20 Generally, when an impairment is considered permanent, the injuries will also be stabilised. However, there could be cases where an impairment is considered permanent because it is unlikely to change in future months regardless of treatment, but the injuries are not stabilised because future treatment is intended and the extent of this is not predictable. For example, for an injured person who suffers an amputation or spinal injury, the impairment is permanent and may be able to be assessed soon after the injury as it is not expected to change regardless of treatment. However, the injuries may not be stabilised for some time as the extent of future treatment and rehabilitation is not known.

1.21 The evaluation should only consider the impairment as it is at the time of the assessment.

1.22 The evaluation must not include any allowance for a predicted deterioration, such as osteoarthritis in a joint many years after an intra-articular fracture, as it is impossible to be precise about any such later alteration. However, it may be appropriate to comment on this possibility in the impairment evaluation report.

Non-assessable injuries

1.23 Certain injuries may not result in an assessable impairment covered by these Guidelines and the AMA4 Guides. For example, uncomplicated healed sternal and rib fractures do not result in any assessable impairment.

Impairments not covered by these Guidelines and the AMA4 Guides

1.24 A condition may present that is not covered in these Guidelines or the AMA4 Guides. If objective clinical findings of such a condition are present, indicating the presence of an impairment, then assessment by analogy to a similar condition is appropriate. The medical assessor must include the rationale for the methodology chosen in the impairment evaluation report.

Adjustment for the effects of treatment or lack of treatment

1.25 The results of past treatment (for example, operations) must be considered since the injured person is being evaluated as they present at the time of assessment.

1.26 Where the effective long-term treatment of an injury results in apparent, substantial or total elimination of a physical permanent impairment, but the injured person is likely to revert to the fully impaired state if treatment is withdrawn, the medical assessor may increase the percentage of WPI by 1%, 2% or 3% WPI. This percentage must be combined with any other impairment percentage using the ‘Combined values’ chart (pages 322–324, AMA4 Guides). An example might be long-term drug treatment for epilepsy. This clause does not apply to the use of analgesics or anti-inflammatory drugs for pain relief.

1.27 For adjustment for the effects of treatment on a permanent psychiatric impairment, refer to clauses 1.222 to 1.224 under ‘Mental and behavioural disorders’ within this part of the Motor Accident Guidelines.

1.28 If an injured person has declined a particular treatment or therapy that the medical assessor believes would be beneficial, this should not change the impairment estimate. However, a comment on the matter should be included in the impairment evaluation report.

1.29 Equally, if the medical assessor believes substance abuse is a factor influencing the clinical state of the injured person, a comment on the matter should be included in the impairment evaluation report.

Adjustment for the effects of prostheses or assistive devices

1.30 Whenever possible, the impairment assessment should be conducted without assistive devices, except where these cannot be removed. The visual system must be assessed in accordance with clauses 1.242 to 1.243 in this Part of the Motor Accident Guidelines.

Pre-existing impairment

1.31 The evaluation of the permanent impairment may be complicated by the presence of an impairment in the same region that existed before the relevant motor accident. If there is objective evidence of a pre-existing symptomatic permanent impairment in the same region at the time of the accident, then its value must be calculated and subtracted from the current WPI value. If there is no objective evidence of the pre-existing symptomatic permanent impairment, then its possible presence should be ignored.

1.32 The capacity of a medical assessor to determine a change in physical impairment will depend upon the reliability of clinical information on the pre‑existing condition. To quote the AMA4 Guides (page 10): ‘For example, in apportioning a spine impairment, first the current spine impairment would be estimated, and then impairment from any pre-existing spine problem would be estimated. The estimate for the pre-existing impairment would be subtracted from that for the present impairment to account for the effects of the former. Using this approach to apportionment would require accurate information and data on both impairments.’ Refer to clause 1.218 for the approach to a pre-existing psychiatric impairment.

1.33 Pre-existing impairments should not be assessed if they are unrelated or not relevant to the impairment arising from the motor accident.

Subsequent injuries

1.34 The evaluation of permanent impairment may be complicated by the presence of an impairment in the same region that has occurred subsequent to the relevant motor accident. If there is objective evidence of a subsequent and unrelated injury or condition resulting in permanent impairment in the same region, its value should be calculated. The permanent impairment resulting from the relevant motor accident must be calculated. If there is no objective evidence of the subsequent impairment, its possible presence should be ignored.

Psychiatric impairment

1.35 Psychiatric impairment is assessed in accordance with ‘Mental and behavioural disorders’ within this part of the Motor Accident Guidelines.

Psychiatric and physical impairments

1.36 Impairment resulting from a physical injury must be assessed separately from the impairment resulting from a psychiatric or psychological injury (see Section 1.7(2) of the Act).

1.37 When determining whether the degree of permanent impairment of the injured person resulting from the motor accident is greater than 10%, the impairment rating for a physical injury cannot be combined with the impairment rating for a psychiatric or psychological injury.

Pain

1.38 Some tables require the pain associated with a particular neurological impairment to be assessed. Because of the difficulties of objective measurement, medical assessors must not make separate allowance for permanent impairment due to pain, and Chapter 15 of the AMA4 Guides must not be used. However, each chapter of the AMA4 Guides includes an allowance for associated pain in the impairment percentages.

Rounding up or down

1.39 The AMA4 Guides (page 9) permit (but do not require) that a final WPI may be rounded to the nearest percentage ending in 0 or 5. This could cause inconsistency between two otherwise identical assessments. For this reason, medical assessors must not round WPI values at any point of the assessment process. During the impairment calculation process, however, fractional values might occur when evaluating the regional impairment (for example, an upper extremity impairment value of 13.25%) and this should be rounded (in this case to 13%). WPI values can only be integers (not fractions).

Consistency

1.40 Tests of consistency, such as using a goniometer to measure range of motion, are good but imperfect indicators of the injured person’s efforts. The medical assessor must use the entire gamut of clinical skill and judgement in assessing whether or not the results of measurements or tests are plausible and relate to the impairment being evaluated. If, in spite of an observation or test result, the medical evidence appears not to verify that an impairment of a certain magnitude exists, the medical assessor should modify the impairment estimate accordingly, describe the modification and outline the reasons in the impairment evaluation report.

1.41 Where there are inconsistencies between the medical assessor’s clinical findings and information obtained through medical records and/or observations of non-clinical activities, the inconsistencies must be brought to the injured person’s attention; for example, inconsistency demonstrated between range of shoulder motion when undressing and range of active shoulder movement during the physical examination. The injured person must have an opportunity to confirm the history and/or respond to the inconsistent observations to ensure accuracy and procedural fairness.

Assessment of children

1.42 The determination of the degree of permanent impairment in children may be impossible in some instances due to the natural growth and development of the child (examples are injuries to growth plates of bones or brain damage). In some cases, the effects of the injury may not be considered permanent and the assessment of permanent impairment may be delayed until growth and development is complete.

Additional investigations

1.43 The injured person who is being assessed should attend with radiological and medical imaging. It is not appropriate for a medical assessor to order additional investigations such as further spinal imaging.

1.44 There are some circumstances where testing is required as part of the impairment assessment; for example, respiratory; cardiovascular; ophthalmology; and ear, nose and throat (ENT). In these cases, it is appropriate to conduct the prescribed tests as part of the assessment.

Combining values

1.45 In general, when separate impairment percentages are obtained for various impairments being assessed, these are not simply added together, but must be combined using the ‘Combined values’ chart (pages 322–324, AMA4 Guides). This process is necessary to ensure the total whole person or regional impairment does not exceed 100% of the person or region. The calculation becomes straightforward after working through a few examples (for instance, page 53 of the AMA4 Guides). Note however, that in a few specific instances, for example for ranges of motion of the thumb joints (AMA4 Guides, page 16), the impairment values are directly added. Multiple impairment scores should be treated precisely as the AMA4 Guides or these Guidelines instruct.

Lifetime Care & Support Scheme

1.46 An injured person who has been accepted as a lifetime participant of the Lifetime Care & Support Scheme under Section 9 of the Motor Accidents (Lifetime Care and Support) Act 2006 (NSW) has a degree of permanent impairment greater than 10%.

Upper extremity

Introduction

1.47 The hand and upper extremity are discussed in Section 3.1 of Chapter 3 of the AMA4 Guides (pages 15–74). This section provides guidance on methods of assessing permanent impairment involving the upper extremity. It is a complex section that requires an organised approach with careful documentation of findings.

Assessment of the upper extremity

1.48 Assessment of the upper extremity involves a physical evaluation that can use a variety of methods. The assessment, in this Part of the Motor Accident Guidelines, does not include a cosmetic evaluation, which should be done with reference to ‘Other body systems’ within this part of the Motor Accident Guidelines and Chapter 13 of the AMA4 Guides.

1.49 The assessed impairment of a part or region can never exceed the impairment due to amputation of that part or region. For an upper limb, therefore, the maximum evaluation is 60% WPI.

1.50 Although range of motion appears to be a suitable method for evaluating impairment, it can be subject to variation because of pain during motion at different times of examination and/or a possible lack of cooperation by the person being assessed. Range of motion is assessed as follows:

1.50.1 A goniometer should be used where clinically indicated.

1.50.2 Passive range of motion may form part of the clinical examination to ascertain clinical status of the joint, but impairment should only be calculated using active range of motion measurements.

1.50.3 If the medical assessor is not satisfied that the results of a measurement are reliable, active range of motion should be measured with at least three consistent repetitions.

1.50.4 If there is inconsistency in range of motion, then it should not be used as a valid parameter of impairment evaluation. Refer to clause 1.40 of these Guidelines.

1.50.5 If range of motion measurements at examination cannot be used as a valid parameter of impairment evaluation, the medical assessor should then use discretion in considering what weight to give other available evidence to determine if an impairment is present.

1.51 If the contralateral uninjured joint has a less than average mobility, the impairment value(s) corresponding with the uninjured joint can serve as a baseline and are subtracted from the calculated impairment for the injured joint only if there is a reasonable expectation that the injured joint would have had similar findings to the uninjured joint before injury. The rationale for this decision must be explained in the impairment evaluation report.

1.52 When using clause 1.51 (above), the medical assessor must subtract the total upper extremity impairment (UEI) for the uninjured joint from the total UEI for the injured joint. The resulting percentage UEI is then converted to WPI. Where more than one joint in the upper limb is injured and clause 1.51 is used, clause 1.51 must be applied to each joint.

1.53 Figure 1 of the AMA4 Guides (pages 16–17) is extremely useful to document findings and guide assessment of the upper extremity. Note, however, that the final summary part of Figure 1 (pages 16–17, AMA4 Guides) does not make it clear that impairments due to peripheral nerve injuries cannot be combined with other impairments in the upper extremities unless they are separate injuries.

1.54 The hand and upper extremity are divided into the regions of the thumb, fingers, wrist, elbow and shoulder. The medical assessor must follow the instructions in Figure 1 (pages 16–17, AMA4 Guides) regarding adding or combining impairments.

1.55 Measurements of radial and ulnar deviation must not be rounded to the nearest 10°. The measurement of radial and ulnar deviation must be rounded to the nearest 5° and the appropriate impairment rating read from Figure 29 (page 38, AMA4 Guides).

1.56 Table 3 (page 20, AMA4 Guides) is used to convert UEI to WPI. Note that 100% UEI is equivalent to 60% WPI.

1.57 If the condition is not in the AMA4 Guides it may be assessed using another like condition. For example, a rotator cuff injury may be assessed by impairment of shoulder range of movement or other disorders of the upper extremity (pages 58–64, AMA4 Guides).

Specific interpretation of the AMA4 Guides

Impairment of the upper extremity due to peripheral nerve disorders

1.58 If an impairment results solely from a peripheral nerve injury, the medical assessor must not evaluate impairment from Sections 3.1f to 3.1j (pages 24–45, AMA4 Guides). Section 3.1k and subsequent sections must be used for evaluation of such impairment. For peripheral nerve lesions, use Table 15 (page 54, AMA4 Guides) together with Tables 11a and 12a (pages 48–49, AMA4 Guides) for evaluation. Table 16 (page 57, AMA4 Guides) must not be used.

1.59 When applying Tables 11a and 12a (pages 48–49, AMA4 Guides), the maximum value for each grade must be used unless assessing complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

1.60 For the purposes of interpreting Table 11 (page 48, AMA4 Guides), abnormal sensation> includes disturbances in sensation such as dysaesthesia, paraesthesia and cold intolerance. Decreased sensibility includes anaesthesia and hypoaesthesia.

Impairment of the upper extremity due to CRPS

1.61 The section, ‘Causalgia and reflex sympathetic dystrophy’ (page 56, AMA4 Guides) must not be used.These conditions have been better defined since the AMA4 Guides were published. The current terminology is CRPS type I (referring to what was termed reflex sympathetic dystrophy) and CRPS type II (referring to what was termed causalgia).

1.62 For a diagnosis of CRPS at least eight of the following 11 criteria must be present: skin colour is mottled or cyanotic; cool skin temperature; oedema; skin is dry or overly moist; skin texture is smooth and non-elastic; soft tissue atrophy (especially fingertips); joint stiffness and decreased passive motion; nail changes with blemished, curved or talon-like nails; hair growth changes with hair falling out, longer or finer; X-rays showing trophic bone changes or osteoporosis; and bone scan showing findings consistent with CRPS.

1.63 When the diagnosis of CRPS has been established, impairment due to CRPS type I is evaluated as follows:

1.63.1 Rate the UEI resulting from the loss of motion of each individual joint affected by CRPS.

1.63.2 Rate the UEI resulting from sensory deficits and pain according to the grade that best describes the severity of interference with activities of daily living as described in Table 11a (page 48, AMA4 Guides). The maximum value is not applied in this case (clause 1.59 above). The value selected represents the UEI. A nerve multiplier is not used.

1.63.3 Combine the upper extremity value for loss of joint motion (clause 1.63.1) with the value for pain and sensory deficits (clause 1.63.2) using the ‘Combined values’ chart (pages 322–324, AMA4 Guides).

1.63.4 Convert the UEI to WPI by using Table 3 (page 20, AMA4 Guides).

1.64 When the diagnosis of CRPS has been established, impairment due to CRPS type II is evaluated as follows:

1.64.1 Rate the UEI resulting from the loss of motion of each individual joint affected by CRPS.

1.64.2 Rate the UEI resulting from sensory deficits and pain according to the methods described in Section 3.1k (pages 46–56, AMA4 Guides) and Table 11a (page 48, AMA4 Guides).

1.64.3 Rate the UEI upper extremity impairment resulting from motor deficits and loss of power of the injured nerve according to the determination method described in Section 3.1k (pages 46–56, AMA4 Guides) and Table 12a (page 49, AMA4 Guides).

1.64.4 Combine the UEI percentages for loss of joint motion (clause 1.64.1), pain and sensory deficits (clause 1.64.2) and motor deficits (clause 1.64.3) using the ‘Combined values’ chart (pages 322–324, AMA4 Guides).

1.64.5 Convert the UEI to WPI by using Table 3 (page 20, AMA4 Guides).

Impairment due to other disorders of the upper extremity

1.65 Section 3.1m ‘Impairment due to other disorders of the upper extremity, (pages 58–64, AMA4 Guides) should be rarely used in the context of motor accident injuries. The medical assessor must take care to avoid duplication of impairments.

1.66 Radiographs for carpal instability (page 61, AMA4 Guides) should only be considered if available, along with the clinical signs.

1.67 Strength evaluations and Table 34 (pages 64–65, AMA4 Guides) must not be used as they are unreliable indicators of impairment. Where actual loss of muscle bulk has occurred, the assessment can be completed by analogy, for example with a relevant peripheral nerve injury. Similar principles can be applied where tendon transfers have been performed or after amputation reattachment if no other suitable methods of impairment evaluation are available.

Lower extremity

Introduction

1.68 The lower extremity is discussed in Section 3.2 of Chapter 3 in the AMA4 Guides (pages 75–93). This section provides a number of alternative methods of assessing permanent impairment involving the lower extremity. It is a complex section that requires an organised approach. A lower extremity worksheet may be included as provided in these Guidelines at Table 6. Each method should be calculated in lower extremity impairment percentages and then converted to WPI using Table 4 in these Guidelines.

Assessment of the lower extremity

1.69 Assessment of the lower extremity involves a physical evaluation that can use a variety of methods. In general, the method that most specifically addresses the impairment should be used. For example, impairment due to a peripheral nerve injury in the lower extremity should be assessed with reference to that nerve rather than by its effect on gait.

1.70 There are several different forms of evaluation that can be used as indicated in Sections 3.2a to 3.2m (pages 75–89, AMA4 Guides). Table 5 in these Guidelines indicates which evaluation methods can and cannot be combined for the assessment of each injury. This table can only be used to assess one combination at a time. It may be possible to perform several different evaluations as long as they are reproducible and meet the conditions specified below and in the AMA4 Guides. The most specific method, or combination of methods, of impairment assessment should be used. However, when more than one equally specific method or combination of methods of rating the same impairment is available, the method providing the highest rating should be chosen. Table 6 can be used to assist the process of selecting the most appropriate method(s) of rating lower extremity impairment.

1.71 If there is more than one injury in the limb, each injury is to be assessed separately and then the WPIs combined. For example, a fractured tibial plateau and laxity of the medial collateral ligament are separately assessed and their WPI combined.

1.72 If the contralateral uninjured joint has a less than average mobility, the impairment value(s) corresponding with the uninjured joint can serve as a baseline and are subtracted from the calculated impairment for the injured joint, only if there is a reasonable expectation that the injured joint would have had similar findings to the uninjured joint before injury. The rationale for this decision must be explained in the impairment evaluation report.

1.73 The assessed impairment of a part or region can never exceed the impairment due to amputation of that part or region. For a lower limb, therefore, the maximum evaluation is 40% WPI.

1.74 When the ‘Combined values’ chart is used, the medical assessor must ensure that the values all relate to the same system (i.e. WPI or lower extremity impairment or foot impairment). Lower extremity impairment can then be combined with impairments in other parts of the body using the same table and ensuring only WPIs are combined.

1.75 Refer to Table 5 to determine which impairments can and cannot be combined.

Specific interpretation of the AMA4 Guides

Leg length discrepancy

1.76 When true leg length discrepancy is determined clinically (page 75, AMA4 Guides), the method used must be indicated (for example, tape measure from anterior superior iliac spine to medial malleolus). Clinical assessment of legislation length discrepancy is an acceptable method, but if computerised tomography films are available they should be used in preference, but only when there are no fixed deformities that would make them clinically inaccurate.

1.77 Table 35 (page 75, AMA4 Guides) must have the element of choice removed such that impairments for leg length should be read as the higher figure of the range quoted, being 0, 3, 5, 7 or 8 for WPI, or 0, 9, 14, 19 or 20 for lower limb impairment.

Gait derangement

1.78 Assessment of impairment based on gait derangement should be used as the method of last resort (pages 75–76, AMA4 Guides). Methods most specific to the nature of the disorder must always be used in preference. If gait derangement is used, it cannot be combined with any other impairment evaluation in the lower extremity. It can only be used if no other valid method is applicable, and reasons why it was chosen must be provided in the impairment evaluation report.

1.79 The use of any walking aid must be necessary and permanent.

1.80 Item b of Table 36 (page 76, AMA4 Guides) is deleted as the Trendelenburg sign is not sufficiently reliable.

Muscle atrophy (unilateral)

1.81 This Section (page 76, AMA4 Guides) is not applicable if the limb other than that being assessed is abnormal (for example, if varicose veins cause swelling, or if there are other injuries).

1.82 Table 37 ‘Impairments from leg muscle atrophy’ (page 77, AMA4 Guides) must not be used. Unilateral leg muscle atrophy must be assessed using Table 1(a) and (b) (below).

Table 1(a): Impairment due to unilateral leg muscle atrophy

Thigh: The circumference is measured 10 cm above the patella with the knee fully extended and the muscles relaxed.

Difference in circumference (cm) | Impairment degree | Whole person impairment (%) | Lower extremity impairment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

0–0.9 | None | 0 | 0 |

1–1.9 | Mild | 2 | 6 |

2–2.9 | Moderate | 4 | 11 |

3+ | Severe | 5 | 12 |

Table 1(b): Impairment due to unilateral leg muscle atrophy

Calf: The maximum circumference on the normal side is compared with the circumference at the same level on the affected side.

Difference in circumference (cm) | Impairment degree | Whole person impairment (%) | Lower extremity impairment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

0–0.9 | None | 0 | 0 |

1–1.9 | Mild | 2 | 6 |

2–2.9 | Moderate | 4 | 11 |

3+ | Severe | 5 | 12 |

Manual muscle strength testing

1.83 The Medical Research Council (MRC) grades for muscle strength are universally accepted. They are not linear in their application, but ordinal. The descriptions in Table 38 (page 77, AMA4 Guides) are to be used. The results of electrodiagnostic methods and tests are not to be considered in the evaluation of muscle testing, which is performed manually. Table 39 (page 77, AMA4 Guides) is to be used for this method of evaluation.

Range of motion

1.84 Although range of motion (pages 77–78, AMA4 Guides) appears to be a suitable method for evaluating impairment, it can be subject to variation because of pain during motion at different times of examination and/or a possible lack of cooperation by the injured person being assessed. Range of motion is assessed as follows:

1.84.1 A goniometer should be used where clinically indicated.

1.84.2 Passive range of motion may form part of the clinical examination to ascertain clinical status of the joint, but impairment should only be calculated using active range of motion measurements.

1.84.3 If the medical assessor is not satisfied that the results of a measurement are reliable, active range of motion should be measured with at least three consistent repetitions.

1.84.4 If there is inconsistency in range of motion, then it should not be used as a valid parameter of impairment evaluation. Refer to clause 1.40 of these Guidelines.

1.84.5 If range of motion measurements at examination cannot be used as a valid parameter of impairment evaluation, the medical assessor should then use discretion in considering what weight to give other evidence available to determine if an impairment is present.

1.85 Tables 40 to 45 (page 78, AMA4 Guides) are used to assess range of motion in the lower extremities. Where there is loss of motion in more than one direction/axis of the same joint, only the most severe deficit is rated – the ratings for each motion deficit are not added or combined. However, motion deficits arising from separate tables can be combined.

Ankylosis

1.86 For the assessment of impairment when a joint is ankylosed (pages 79–82, AMA4 Guides), the calculation to be applied is to select the impairment if the joint is ankylosed in optimum position and then, if not ankylosed in the optimum position (Table 6.2), by adding (not combining) the values of WPI using Tables 46–61 (pages 79–82, AMA4 Guides). Note: The example listed under the heading ‘Hip’ on page 79 of the AMA4 Guides is incorrect.

Table 2: Impairment for ankylosis in the optimum position

Joint | Whole person (%) | Lower extremity (%) | Ankle or foot (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Hip | 20 | 50 | – |

Knee | 27 | 67 | – |

Ankle | 4 | 10 | 14 |

Foot | 4 | 10 | 14 |

1.87 Note that the WPI from ankylosis of a joint, or joints, in the lower limb cannot exceed 40% WPI or 100% lower limb impairment. If this figure is exceeded when lower limb impairments are combined, then only 40% can be accepted as the maximum WPI.

Arthritis

1.88 Impairment due to arthritis (pages 82–83, AMA4 Guides) can be assessed by measuring the distance between the subchondral bone ends (joint space) if radiography is performed in defined positions. It indicates the thickness of articular cartilage. No notice is to be taken of other diagnostic features of arthritis such as osteophytes or cystic changes in the bone.

1.89 Hip radiography can be done in any position of the hip, but specified positions for the knee and ankle (page 82, AMA4 Guides) must be achieved by the radiographer.

1.90 Table 62 (page 83, AMA4 Guides) indicates the impairment assessment for arthritis based on articular cartilage thickness.

1.91 If arthritis is used as the basis for impairment assessment in this way, then the rating cannot be combined with gait derangement, muscle atrophy, muscle strength or range of movement assessments. It can be combined with a diagnosis-based estimate (Table 5).

1.92 When interpreting Table 62 (page 83, AMA4 Guides), if the articular cartilage interval is not a whole number, round to the higher impairment figure.

Amputation

1.93 Where there has been amputation of part of a lower extremity Table 63 applies (page 83, AMA4 Guides). The references to 3 inches below knee amputation should be converted to 7.5 centimetres.

Diagnosis-based estimates (lower extremity)

1.94 Section 3.2i (pages 84–88, AMA4 Guides) lists a number of conditions that fit a category of diagnosis-based estimates. They are listed in Table 64 (pages 85–86, AMA4 Guides). It is essential to read the footnotes.

1.95 It is possible to combine impairments from Table 64 for diagnosis-based estimates with other injuries (for example, nerve injury) using the ‘Combined values’ chart (pages 322–324, AMA4 Guides).

1.96 Pelvic fractures must be assessed using Section 3.4 (page 131, AMA4 Guides). Fractures of the acetabulum should be assessed using Table 64 (pages 85‑86, AMA4 Guides).

1.97 Residual signs must be present at examination and may include anatomically plausible tenderness, clinically obvious asymmetry, unilateral limitation of hip joint range of motion not associated with fractured acetabulum and/or clear evidence of malalignment.

1.98 Where both collateral and cruciate ligament laxity of mild severity is present, these must be assessed separately as 3% WPI for each ligament and then combined, resulting in a total of 6% WPI.

1.99 Rotational deformity following tibial shaft fracture must be assessed analogously to Table 64 ‘Tibial shaft fracture, malalignment of’ (page 85, AMA4 Guides).

1.100 To avoid the risk of double assessment, if avascular necrosis of the talus is used as the basis for assessment, it cannot be combined with intra-articular fracture of the ankle with displacement or intra-articular fracture of the hind foot with displacement in Table 64, column 1 (page 86, AMA4 Guides).

1.101 Tables 65 and 66 (pages 87–88, AMA4 Guides) use a different method of assessment. A point score system is applied, and then the total of points calculated for the hip or knee joint respectively is converted to an impairment rating from Table 64. Tables 65 and 66 refer to the hip and knee joint replacement respectively. Note that while all the points are added in Table 65, some points are deducted when Table 66 is used.

1.102 In Table 65 references to distance walked under ‘b. Function’, six blocks should be construed as being 600 metres, and three blocks being 300 metres.

Skin loss (lower extremity)

1.103 Skin loss can only be included in the calculation of impairment if it is in certain sites and meets the criteria listed in Table 67 (page 88, AMA4 Guides). Scarring otherwise in the lower extremity must be assessed with reference to ‘Other body systems’ within this part of the Motor Accident Guidelines.

Impairment of the lower extremity due to peripheral nerve injury

1.104 Peripheral nerve injury should be assessed by reference to Section 3.2k (pages 88–89, AMA4 Guides). Separate impairments for the motor, sensory and dysaesthetic components of nerve dysfunction in Table 68 (page 89, AMA4 Guides) are combined.

1.105 The posterior tibial nerve is not included in Table 68, but its contribution can be calculated by subtracting common peroneal nerves rating from sciatic nerve rating as shown in Table 6.3 (below). The values in brackets are lower extremity impairment values.

Table 3: Impairment for selected lower extremity peripheral nerves

Nerve | Motor % | Sensory % | Dysaesthesia % |

|---|---|---|---|

Sciatic nerve | 30 (75) | 7 (17) | 5 (12) |

Common peroneal nerve | 15 (42) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) |

Tibial nerve | 15 (33) | 5 (12) | 3 (7) |

1.106 Peripheral nerve injury impairments can be combined with other impairments, but not those for muscle strength, gait derangement, muscle atrophy and CRPS, as shown in Table 5. When using Table 68, refer to Tables 11a and 12a (pages 48–49, AMA4 Guides) and clauses 1.58, 1.59 and 1.60 of these Guidelines.

Impairment of the lower extremity due to CRPS

1.107 The Section ‘Causalgia and reflex sympathetic dystrophy’ (page 89, AMA4 Guides) must not be used. These conditions have been better defined since the AMA4 Guides were published. The current terminology is CRPS type I (referring to what was termed reflex sympathetic dystrophy) and CRPS type II (referring to what was termed causalgia).

1.108 When complex CRPS occurs in the lower extremity it must be evaluated as for the upper extremity using clauses 1.61–1.64 within this part of the Motor Accident Guidelines.

Impairment of the lower extremity due to peripheral vascular disease

1.109 Lower extremity impairment due to peripheral vascular disease is evaluated using Table 69 (page 89, AMA4 Guides). Table 14 (page 198, AMA4 Guides) must not be used. In Table 69, there is a range of lower extremity impairments, not WPI, within each of the classes 1 to 5. Where there is a range of impairment percentages listed, the medical assessor must nominate an impairment percentage based on the complete clinical circumstances revealed during the examination and provide reasons.

1.110 Lower extremity impairment values must be converted to WPI using

Table 6.4.

Download a PDF of this table in full.

Download a PDF of this table in full.

Table 6: Lower extremity worksheet

Line | Impairment | Table | AMA4 | Potential impairment | Selected impairment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | Gait derangement | 36 | 76 | ||

2 | Unilateral muscle atrophy | 37 | 77 | ||

3 | True muscle weakness | 39 | 77 | ||

4 | Range of motion | 40–45 | 78 | ||

5 | Joint ankylosis | 46–61 | 79–82 | ||

6 | Arthritis | 62 | 83 | ||

7 | Amputation | 63 | 83 | ||

8 | Diagnosis-based estimates | 64 | 85–86 | ||

9 | Limb length discrepancy | 35 | 75 | ||

10 | Skin loss | 67 | 88 | ||

11 | Peripheral nerve deficit | 68 | 89 | ||

12 | Peripheral vascular disease | 69 | 89 | ||

13 | Complex regional pain syndrome | AMA4 |

Spine

Introduction

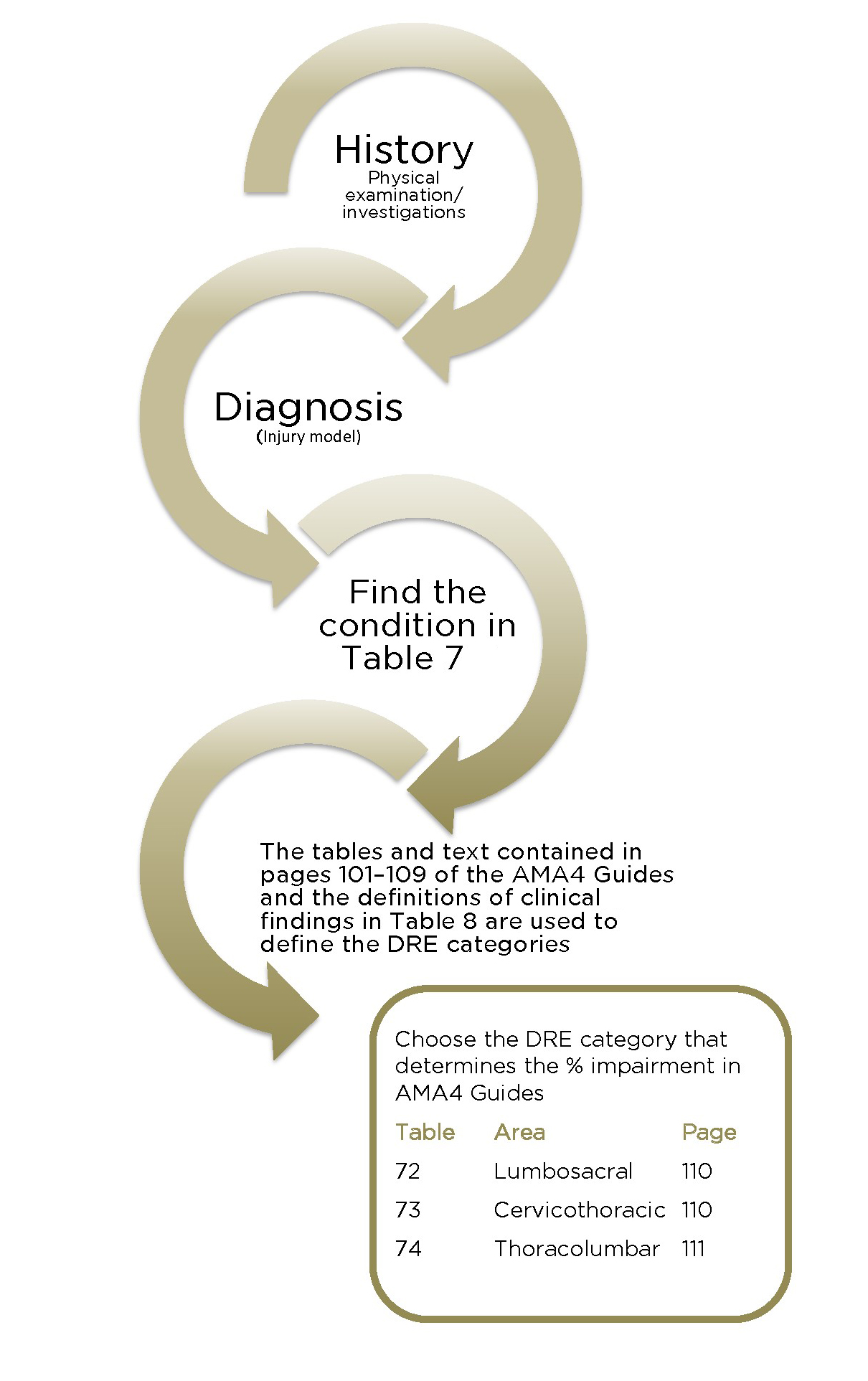

1.111 The spine is discussed in Section 3.3 of Chapter 3 in the AMA4 Guides (pages 94–138). That chapter presents several methods of assessing impairments of the spine. Only the diagnosis-related estimate (DRE) method is to be used for evaluating impairment of the spine, as modified by this Part of the Motor Accident Guidelines. The AMA4 Guides use the term injury modelfor this method.

1.112 The injury model relies especially on evidence of neurological deficits and uncommon, adverse structural changes, such as fractures and dislocations. Under this model, DREs are differentiated according to clinical findings that are verifiable using standard medical procedures.

1.113 The assessment of spinal impairment is made at the time the injured person is examined. If surgery has been performed, then the effect of the surgery, as well as the structural inclusions, must be taken into consideration when assessing impairment. Refer also to clause 1.20 in these Guidelines.

1.114 Medical assessors must consider whether any pre-existing spinal condition or surgery is related to the motor accident, is symptomatic and whether this would result in any or total apportionment. Where a pre-existing spinal condition, or spinal surgery, is unrelated to the injury from the relevant motor accident, the medical assessor should rely on clause 1.33.

1.115 The AMA4 Guides use the terms cervicothoracic, thoracolumbar and lumbosacral for the three spine regions. These terms relate to the cervical, thoracic and lumbar regions respectively.

Assessment of the spine

1.116 The range of motion (ROM) model and Table 75 are not to be used for spinal impairment evaluation (pages 112–130, AMA4 Guides).

1.117 The medical assessor may consider Table 7 (below) to establish the appropriate category for the spine impairment. Its principal difference from Table 70 (page 108, AMA4 Guides) is the removal of the term motion segment integrity wherever it appears (see clause 1.123).

Table 7: Assessing spinal impairment – DRE category

Injured person’s condition | I | II | III | IV | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Low back pain, neck pain, back pain or symptoms | I | ||||

Vertebral body compression < 25% | II | ||||

Low back pain or neck pain with guarding or | II | ||||

Posterior element fracture, healed, stable, no dislocation or radiculopathy | II | ||||

Transverse or spinous process fracture with displacement of fragment, healed, stable | II | ||||

Low back or neck pain with radiculopathy | III | ||||

Vertebral body compression fracture 25–50% | III | ||||

Posterior element fracture with spinal canal deformity or radiculopathy, stable, healed | III | ||||

Radiculopathy | III | ||||

Vertebral body compression > 50% | IV | V | |||

Multilevel structural compromise | IV | V | |||

Spondylolysis with radiculopathy | III | IV | V | ||

Spondylolisthesis without radiculopathy | I | II | |||

Spondylolisthesis with radiculopathy | III | IV | V | ||

Vertebral body fracture without radiculopathy | II | III | IV | ||

Vertebral body fracture with radiculopathy | III | IV | V | ||

Vertebral body dislocation without radiculopathy | II | III | IV | ||

Vertebral body dislocation with radiculopathy | III | IV | V | ||

Previous spine operation without radiculopathy | II | III | IV | ||

Previous spine operation with radiculopathy | III | IV | V | ||

Stenosis, facet arthrosis or disease | I | II | |||

Stenosis, facet arthrosis or disease with radiculopathy | III |

1.118 The evaluation must not include any allowance for predicted long-term change. For example, a spinal stenosis syndrome after vertebral fracture or increased back pain due to osteoarthritis of synovial joints after intervertebral disc injury must not be factored in to the impairment evaluation.

1.119 All impairments in relation to the spine should be calculated in terms of WPI and assessed in accordance with clauses 1.1 to 1.46 within these Motor Accident Guidelines and Chapter 3.3 of AMA4 Guides.

1.120 The assessment should include a comprehensive accurate history, a review of all relevant records available at the assessment, a comprehensive description of the individual’s current symptoms, a careful and thorough physical examination and all findings of relevant diagnostic tests available at the assessment. Imaging findings that are used to support the impairment rating should be concordant with symptoms and findings on examination. The medical assessor should record whether diagnostic tests and radiographs were seen or whether they relied on reports.

1.121 While imaging and other studies may assist medical assessors in making a diagnosis, it is important to note that the presence of a morphological variation from what is called normal in an imaging study does not make the diagnosis. Several reports indicate that approximately 30% of people who have never had back pain will have an imaging study that can be interpreted as positive for a herniated disc, and 50% or more will have bulging discs. Further, the prevalence of degenerative changes, bulges and herniations increases with advancing age. To be of diagnostic value, imaging findings must be concordant with clinical symptoms and signs, and the history of injury. In other words, an imaging test is useful to confirm a diagnosis, but an imaging result alone is insufficient to qualify for a DRE category.

1.122 The medical assessor must include in the report a description of how the impairment rating was calculated, with reference to the relevant tables and/or figures used.

Specific interpretation of the AMA4 Guides

Loss of motion segment integrity

1.123 The Section ‘Loss of motion segment integrity’ (pages 98–99, AMA4 Guides) and all subsequent references to it must not be applied, as the injury model (DRE method) covers all relevant conditions.

Definitions of clinical findings used to place an individual in a DRE category

1.124 Definitions of clinical findings, which are used to place an individual in a DRE category are provided in Table 8 (below). A definition of a muscle spasm has been included; however, it is not a clinical finding used to place an individual in a DRE category.

Table 8: Definitions of clinical findings

Term | Definition |

|---|---|

Atrophy | Atrophy is measured with a tape measure at identical levels on both limbs. For reasons of reproducibility, the difference in circumference should be 2 cm or greater in the thigh and 1 cm or greater in the arm, forearm or calf. The medical assessor can address asymmetry due to extremity dominance in the report. Measurements should be recorded to the nearest 0.5 cm. The atrophy should be clinically explicable in terms of the relevant nerve root affected. |

Muscle guarding | Guarding is a contraction of muscle to minimise motion or agitation of the injured or diseased tissue. It is not a true muscle spasm because the contraction can be relaxed. In the lumbar spine, the contraction frequently results in loss of the normal lumbar lordosis, and it may be associated with reproducible loss of spinal motion. |

Muscle spasm | Muscle spasm is a sudden, involuntary contraction of a muscle or a group of muscles. Paravertebral muscle spasm is common after acute spinal injury but is rare in chronic back pain. It is occasionally visible as a contracted paraspinal muscle but is more often diagnosed by palpation (a hard muscle). To differentiate true muscle spasm from voluntary muscle contraction, the individual should not be able to relax the contractions. The spasm should be present standing as well as in the supine position and frequently causes scoliosis. The medical assessor can sometimes differentiate spasm from voluntary contraction by asking the individual to place all their weight first on one foot and then the other while the medical assessor gently palpates the paraspinal muscles. With this manoeuvre, the individual normally relaxes the paraspinal muscles on the weight-bearing side. If the medical assessor witnesses this relaxation, it usually means that true muscle spasm is not present. |

Non-uniform loss of spinal motion (dysmetria) | Non-uniform loss of motion of the spine in one of the three principle planes is sometimes caused by muscle spasm or guarding. To qualify as true non-uniform loss of motion, the finding must be reproducible and consistent, and the medical assessor must be convinced that the individual is cooperative and giving full effort. When assessing non-uniform loss of range of motion (dysmetria), medical assessors must include all three planes of motion for the cervicothoracic spine (flexion/extension, lateral flexion and rotation), two planes of motion for the thoracolumbar spine (flexion/extension and rotation) and two planes of motion for the lumbosacral spine (flexion/ extension and lateral flexion). Medical assessors must record the range of spinal motion as a fraction or percentage of the normal range such as cervical flexion is 3/4 or 75% of the normal range. Medical assessors must not refer to body landmarks (such as able to touch toes) to describe the available (or observed) motion. |

Non-verifiable radicular complaints | Non-verifiable radicular complaints are symptoms (for example, shooting pain, burning sensation, tingling) that follow the distribution of a specific nerve root, but there are no objective clinical findings (signs) of dysfunction of the nerve root (for example, loss or diminished sensation, loss or diminished power, loss or diminished reflexes). |

Reflexes | Reflexes may be normal, increased, reduced or absent. For reflex abnormalities to be considered valid, the involved and normal limbs should show marked asymmetry on repeated testing. Abnormal reflexes such as Babinski signs or clonus may be signs of corticospinal tract involvement. |

Sciatic nerve root tension signs | Sciatic nerve tension signs are important indicators of irritation of the lumbosacral nerve roots. While most commonly seen in individuals with a herniated lumbar disc, this is not always the case. In chronic nerve root compression due to spinal stenosis, tension signs are often absent. A variety of nerve tension signs have been described. The most commonly used is the straight leg raising (SLR) test. When performed in the supine position, the hip is flexed with the knee extended. In the sitting position, with the hip flexed 90 degrees, the knee is extended. The test is positive when thigh and/or leg pain along the appropriate dermatomal distribution is reproduced. The degree of elevation at which pain occurs is recorded. Research indicates that the maximum movement of nerve roots occurs when the leg is at an angle of 20 degrees to 70 degrees relative to the trunk. However, this may vary depending on the individual’s anatomy. Further, the L4, L5 and S1 nerve roots are those that primarily change their length when straight leg raising is performed. Thus, pathology at higher levels of the lumbar spine is often associated with a negative SLR test. Root tension signs are most reliable when the pain is elicited in a dermatomal distribution. Back pain on SLR is not a positive test. Hamstring tightness must also be differentiated from posterior thigh pain due to root tension. |

Weakness and loss of sensation | To be valid, the sensory findings must be in a strict anatomic distribution, i.e. follow dermatomal patterns. Motor findings should also be consistent with the affected nerve structure(s). Significant longstanding weakness is usually accompanied by atrophy. |

Diagnosis-related estimates model

1.125 To determine the correct diagnosis-related estimates (DRE) category, the medical assessor may start with Table 7 in these Guidelines, and use this table in conjunction with the DRE descriptors (pages 102–107, AMA4 Guides), as clarified by the definitions in Table 8 (above), with the following amendments to pages 102–107 of the AMA4 Guides:

1.125.1 or history of guarding is deleted from DRE category I for the lumbosacral spine (page 102) and DRE category I for the cervicothoracic spine (page 103)

1.125.2 no significant…roentgenograms is deleted from DRE category I for the lumbosacral spine (page 102) and DRE category I for the cervicothoracic spine (page 103) and DRE categoy I for the thoracolumbar (p106)

1.125.3 documented or as it relates to muscle guarding is deleted from DRE category I for the thoracolumbar spine (page 106)

1.125.4 replace that has been observed and documented by a physician with that has been observed and documented by the medical assessor in DRE category II for the lumbosacral spine (page 102)

1.125.5 replace observed by a physician with observed by the medical assessor in the descriptors for DRE category II for the cervicothoracic spine (page 104) and thoracolumbar spine (page 106)

1.125.6 replace or displacement with with displacement in the descriptors for DRE category II for the thoracolumbar spine (page 106).

1.126 If unable to distinguish between two DRE categories, the higher of those two categories must apply. The inability to differentiate must be noted and explained in the medical assessor’s report.

1.127 Table 71 (page 109, AMA4 Guides) is not to be used. The definitions of clinical findings in Table 8 should be the criteria by which a diagnosis and allocation of a DRE category are made.

Applying the DRE method

1.128 Section 3.3f ‘Specific procedures and directions’ (page 101, AMA4 Guides) indicates the steps that should be followed. Table 7 in these Guidelines is a simplified version of that section, and must be interpreted in conjunction with the amendments listed in clause 1.125 (above).

1.129 DRE I applies when the injured person has symptoms but there are no objective clinical findings by the medical assessor. DRE II applies when there are clinical findings made by the medical assessor, as described in the Sections ‘Description and Verification’ (pages 102–107, AMA4 Guides) with the amendments in clause 1.125, for each of the three regions of the spine. Note that symmetric loss of movement is not dysmetria and does not constitute an objective clinical finding.

1.130 When allocating the injured person to a DRE category, the medical assessor must reference the relevant differentiators and/or structural inclusions.

1.131 Separate injuries to different regions of the spine must be combined.

1.132 Multiple impairments within one spinal region must not be combined. The highest DRE category within each region must be chosen.

Loss of structural integrity

1.133 The AMA4 Guides (page 99) use the term structural inclusionsto define certain spine fracture patterns that may lead to significant impairment and yet not demonstrate any of the findings involving differentiators. Some fracture patterns are clearly described in the examples of DRE categories in Sections 3.3g, 3.3h and 3.3i. They are not the only types of injury in which there is a loss of structural integrity of the spine. In addition to potentially unstable vertebral body fractures, loss of structural integrity can occur by purely soft tissue flexion-distraction injuries.

Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis

1.134 Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are conditions that are often asymptomatic and are present in 5–6% of the population. In assessing their relevance the degree of slip (anteroposterior translation) is a measure of the grade of spondylolisthesis and not in itself evidence of loss of structural integrity. To assess an injured person as having symptomatic spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis requires a clinical assessment as to the nature and pattern of the injury, the injured person’s symptoms and the medical assessor’s findings on clinical examination. Table 8 can be used to allocate spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis to categories I–V depending on the descriptor’s clinical findings in the appropriate DRE. The injured person’s DRE must fit the description of clinical findings described in Table 8.

1.135 Medical assessors should be aware that acute traumatic spondylolisthesis is a rare event.

Sexual functioning

1.136 Sexual dysfunction should only be assessed as an impairment related to spinal injury where there is other objective evidence of spinal cord, cauda equina or bilateral nerve root dysfunction (Table 19, page 149, AMA4 Guides). There is no additional impairment rating for sexual dysfunction in the absence of objective neurological impairment.

1.137 Chapter 11 ‘The urinary and reproductive systems’ of the AMA4 Guides should only be used to assess impairment for impotence where there has been a direct injury to the urinary tract. If this occurs the impairment for impotence must be combined with any spine-related WPI. An example is provided in the AMA4 Guides (page 257) where there is a fracture and dissociation of the symphysis pubis and a traumatic disruption of the urethra.

Radiculopathy

1.138 Radiculopathyis the impairment caused by dysfunction of a spinal nerve root or nerve roots. To conclude that a radiculopathy is present two or more of the following signs should be found:

1.138.1 loss or asymmetry of reflexes (see the definitions of clinical findings in Table 8 in these Guidelines)

1.138.2 positive sciatic nerve root tension signs (see the definitions of clinical findings in Table 8 in these Guidelines)

1.138.3 muscle atrophy and/or decreased limb circumference (see the definitions of clinical findings in Table 8 in these Guidelines)

1.138.4 muscle weakness that is anatomically localised to an appropriate spinal nerve root distribution

1.138.5 reproducible sensory loss that is anatomically localised to an appropriate spinal nerve root distribution.

1.139 Spinal injury causing sensory loss at C2 or C3 must be assessed by firstly using Table 23 (page 152) of the AMA4 Guides, rather than classifying the injury as DRE cervicothoracic category III (radiculopathy). The value must then be combined with the DRE rating for the cervical vertebral injury.

1.140 Note that complaints of pain or sensory features that follow anatomical pathways but cannot be verified by neurological findings do not by themselves constitute radiculopathy. They are described as non-verifiable radicular complaints in the definitions of clinical findings (Table 8 in these Guidelines).

1.141 Global weakness of a limb related to pain or inhibition or other factors does not constitute weakness due to spinal nerve malfunction.

1.142 Electrodiagnostic tests are rarely necessary investigations and a decision about the presence of radiculopathy can generally be made on clinical grounds. The diagnosis of radiculopathy should not be made solely from electrodiagnostic tests.

Multilevel structural compromise

1.143 Multilevel structural compromise (Table 70, page 108, AMA4 Guides) refers to those DREs that are in categories IV and V. It is constituted by structural inclusion, which by definition (page 99, AMA4 Guides) is related to spine fracture patterns and is different from the differentiators and clinical findings in Table 8.

1.1424 Multilevel structural compromise is to be interpreted as fractures of more than one vertebra. To provide consistency of interpretation of the meaning of multiple vertebral fractures, the definition of a vertebral fracture includes any fracture of the vertebral body or of the posterior elements forming the ring of the spinal canal (the pedicle or lamina). It does not include fractures of transverse processes or spinous processes, even at multiple levels (see also clause 1.149 in these Guidelines).

1.145 Multilevel structural compromise also includes spinal fusion and intervertebral disc replacement.

1.146 Multilevel structural compromise or spinal fusion across regions is assessed as if it is in one region. The region giving the highest impairment value must be chosen. A fusion of L5 and S1 is considered to be an intervertebral fusion.

1.147 A vertebroplasty should be assessed on the basis of the fracture for which it was performed.

1.148 Compression fracture: The preferred method of assessing the amount of compression is to use a lateral X-ray of the spinal region with the beam parallel to the disc spaces. If this is not available, a CT scan can be used. Caution should be used in measuring small images as the error rate will be significant unless the medical assessor has the ability to magnify the images electronically. Medical assessors should not rely on the estimated percentage compression reported on the radiology report, but undertake their own measurements to establish an accurate percentage using the following method:

1.148.1 The area of maximum compression is measured in the vertebra with the compression fracture.

1.148.2 The same area of the vertebrae directly above and below the affected vertebra is measured and an average obtained. The measurement from the compressed vertebra is then subtracted from the average of the two adjacent vertebrae. The resulting figure is divided by the average of the two unaffected vertebrae and turned into a percentage.

1.148.3 If there are not two adjacent normal vertebrae, then the next vertebra that is normal and adjacent (above or below the affected vertebra) is used.

The calculations must be documented in the impairment evaluation report.

1.149 Fractures of transverse or spinous processes (one or more) with displacement within a spinal region are assessed as DRE category II because they do not disrupt the spinal canal (pages 102, 104, 106, AMA4 Guides) and they do not cause multilevel structural compromise.

1.150 One or more end-plate fractures in a single spinal region without measurable compression of the vertebral body are assessed as DRE category II.

1.151 In the application of Table 7 regarding multilevel structural compromise:

1.151.1 multiple vertebral fractures without radiculopathy are classed as category IV

1.151.2 multiple vertebral fractures with radiculopathy are classed as category V.

Spinal cord injury

1.152 The assessment of spinal cord injury is covered in clause 1.161 in these Guidelines.

1.153 Cauda equina syndrome: In the AMA4 Guides this term does not have its usual medical meaning. For the purposes of the AMA4 Guides an injured person with cauda equina syndrome has objectively demonstrated permanent partial loss of lower extremity function bilaterally. This syndrome may have associated objectively demonstrated bowel or bladder impairment.

Pelvic fractures

1.154 Pelvic fractures must be assessed using Section 3.4 (page 131, AMA4 Guides). Fractures of the acetabulum must be assessed using Table 64 (pages 85–86, AMA4 Guides).

1.155 Multiple fractures of the pelvis must be assessed separately and then combined.

Figure 1: Spine – summary of spinal DRE assessment

The terms cervicothoracic, thoracolumbar and lumbosacral have been defined in clause 1.115.

Nervous system

Introduction

1.156 Chapter 4 (pages 139–152, AMA4 Guides) provides guidance on methods of assessing permanent impairment involving the central nervous system. Elements of the assessment of permanent impairment involving the peripheral nervous system can be found in relevant parts of the ‘Upper extremity’, ‘Lower extremity’ and ‘Spine’ sections.

1.157 Chapter 4 is logically structured and consistent with the usual sequence of examining the nervous system. Cortical functions are discussed first, followed by the cranial nerves, the brain stem, the spinal cord and the peripheral nervous system.

1.158 Spinal cord injuries (SCI) must be assessed using the ‘Nervous system’ and ‘Musculoskeletal system’ chapters of the AMA4 Guides and these Guidelines. See clause 1.161.

1.159 The relevant parts of the ‘Upper extremity’, ‘Lower extremity’ and ‘Spine’ chapters of the AMA4 Guides must be used to evaluate impairments of the peripheral nervous system.

Assessment of the nervous system

1.160 The introduction to Chapter 4 ‘Nervous system’ in the AMA4 Guides is ambiguous in its statement about combining nervous system impairments. The medical assessor must consider the categories of:

1.160.1 aphasia or communication disorders

1.160.2 mental status and integrative functioning abnormalities

1.160.3 emotional and behavioural disturbances

1.160.4 disturbances of consciousness and awareness (permanent and episodic).

The medical assessor must select the highest rating from categories 1 to 4. This rating can then be combined with ratings of other nervous system impairments or from other body regions.

1.161 A different approach is taken in assessing spinal cord impairment (Section 4.3, pages 147–148, AMA4 Guides). In this case impairments due to this pathology can be combined using the ‘Combined values’ chart (pages 322–324, AMA4 Guides). It should be noted that Section 4.3 ‘Spinal cord’ must be used for motor or sensory impairments caused by a central nervous system lesion. Impairment evaluation of spinal cord injuries should be combined with the associated DRE I–V from Section 3.3 in the ‘Musculoskeletal system’ Chapter (pages 101–107, AMA4 Guides). This section covers hemiplegia due to cortical injury as well as SCI.

1.162 Headache or other pain potentially arising from the nervous system, including migraine, is assessed as part of the impairment related to a specific structure. The AMA4 Guides state that the impairment percentages shown in the chapters of the AMA4 Guides make allowance for the pain that may accompany the impairing condition.

1.163 The ‘Nervous system’ Chapter of the AMA4 Guides lists many impairments where the range for the associated WPI is from 0% to 9% or 0% to 14%. Where there is a range of impairment percentages listed, the medical assessor must nominate an impairment percentage based on the complete clinical circumstances revealed during the examination and provide reasons.

Specific interpretation of the AMA4 Guides

The central nervous system – cerebrum or forebrain

1.164 For an assessment of mental status impairment and emotional and behavioural impairment there should be:

1.164.1 evidence of a significant impact to the head or a cerebral insult, or that the motor accident involved a high-velocity vehicle impact, and

1.164.2 one or more significant, medically verified abnormalities such as an abnormal initial post-injury Glasgow Coma Scale score, or post‑traumatic amnesia, or brain imaging abnormality.

1.165 The results of psychometric testing, if available, must be taken into consideration.

1.166 Assessment of disturbances of mental status and integrative functioning: Table 9 in these Guidelines – the clinical dementia rating (CDR), which combines cognitive skills and function – must be used for assessing disturbances of mental status and integrative functioning.

1.167 When using the CDR the injured person’s cognitive function for each category should be scored independently. The maximum CDR score is 3. Memory is considered the primary category; the other categories are secondary. If at least three secondary categories are given the same numeric score as memory then the CDR = M. If three or more secondary categories are given a score greater or less than the memory score, CDR = the score of the majority of secondary categories unless three secondary categories are scored less than M and two secondary categories are scored greater than M. In this case, then the CDR = M. Similarly if two secondary categories are greater than M, two are less than M and one is the same as M, CDR = M.

1.168 In Table 9, ‘Personal care’ (PC) for the level of impairment is the same for a CDR score of 0 and a CDR score of 0.5, being fully capable of self-care. In order to differentiate between a personal care CDR score of 0 and 0.5, a rating that best fits with the pattern of the majority of other categories must be allocated. For example, when the personal care rating is fully capable of self‑care and at least three other components of the CDR are scored at 0.5 or higher, the PC must be scored at 0.5. If three or more ratings are less than 0.5 then a rating of 0 must be assigned. Reasons to support all ratings allocated must be provided.

1.169 Corresponding impairment ratings for CDR scores are listed in Table 10 in these Guidelines.

1.170 Emotional and behavioural disturbances assessment: Table 3 (page 142, AMA4 Guides) must be used to assess emotional or behavioural disturbances.

1.171 Sleep and arousal disorders assessment: Table 6 (page 143, AMA4 Guides) must be used to assess sleep and arousal disorders. The assessment is based on the clinical assessment normally done for clinically significant disorders of this type.

1.172 Visual impairment assessment: An ophthalmologist must assess all impairments of visual acuity, visual fields or extra-ocular movements (page 144, AMA4 Guides).

1.173 Trigeminal nerve assessment: Sensory impairments of the trigeminal nerve must be assessed with reference to Table 9 (page 145, AMA4 Guides). The words or sensory disturbance are added to the table after the words neuralgic pain in each instance. Impairment percentages for the three divisions of the trigeminal nerve must be apportioned with extra weighting for the first division (for example, division 1 – 40%, and division 2 and 3 – 30% each). If present, motor loss for the trigeminal nerve must be assessed in terms of its impact on mastication and deglutition (page 231, AMA4 Guides).

1.174 As per clause 1.189, regarding bilateral total facial paralysis in Table 4 (page 230, AMA4 Guides) total means all branches of the facial nerve.

1.175 Sexual functioning assessment: Sexual dysfunction is assessed as an impairment only if there is an associated objective neurological impairment (page 149, AMA4 Guides). This is consistent with clauses 1.136 and 1.137 in these Guidelines.

1.176 Olfaction and taste assessment: The assessment of olfaction and taste is covered in clauses 1.192 and 1.193 in these Guidelines.

Download a PDF of this table in full.

Download a PDF of this table in full.

Ear, nose and throat, and related structures

Introduction

1.177 Chapter 9 of the AMA4 Guides (pages 223–234) provides guidance on methods of assessing permanent impairment involving the ear, nose and throat, and related structures, including the face.

1.178 Chapter 9 discusses the ear, hearing, equilibrium, the face, respiratory (air passage) obstruction, mastication and deglutition, olfaction and taste, and speech. There is potential overlap with other chapters, particularly the nervous system, in these areas.

Assessment of ear, nose and throat, and related structures

1.179 To assess impairment of the ear, nose and throat, and related structures, the injured person must be assessed by the medical assessor. While the assessment may be based principally on the results of audiological or other investigations, the complete clinical picture must be elaborated through direct consultation with the injured person by the medical assessor.

Specific interpretation of the AMA4 Guides

Ear and hearing

1.180 Ear and hearing (pages 223–224, AMA4 Guides): Tinnitus is only assessable in the presence of hearing loss, and both must be caused by the motor accident. An impairment of up to 5% can be added, not combined, to the percentage binaural hearing impairment before converting to WPI hearing loss if tinnitus is permanent and severe.

Hearing impairment

1.181 Hearing impairment (pages 224-228, AMA4 Guides): Sections 9.1a and 9.1b of the AMA4 Guides are replaced with the following section.

1.182 Impairment of an injured person’s hearing is determined according to evaluation of the individual’s binaural hearing impairment.

1.183 Hearing impairment must be evaluated when the impairment is permanent. Prosthetic devices (i.e. hearing aids) must not be used during evaluation of hearing sensitivity.

1.184 Hearing threshold level for pure tones is defined as the number of decibels above a standard audiometric zero level for a given frequency at which the listener’s threshold of hearing lies when tested in a suitable sound-attenuated environment. It is the reading on the hearing level dial of an audiometer calibrated according to current Australian standards.

1.185 Binaural hearing impairment is determined by using the 1988 National Acoustics Laboratory tables ‘Improved procedure for determining percentage loss of hearing’, with allowance for presbyacusis according to the presbyacusis correction table in the same publication (NAL Report No. 118, National Acoustics Laboratory, Commonwealth of Australia, 1988).