Print PDF

Home building compensation reform Discussion Paper

Introduction

Businesses in the residential building industry must buy home building compensation insurance for each project they do over $20,000 as a principal contractor (unless the work is of a kind that is exempt from insurance, such as the construction of buildings over three storeys high that contain two or more dwellings). Businesses are only able to buy insurance if they satisfy an insurer’s eligibility criteria. There were 20,133 businesses that were eligible to insure their projects at the end of financial year 2020-21, and 88,270 projects were insured in that year.

The home building compensation scheme (‘HBC scheme’) insures homeowners against the risk the insured business will be unable to complete work or honour statutory warranties due to insolvency, death, disappearance or license suspension for not complying with a court or tribunal order to pay compensation to the homeowner. In financial year 2020-21, the HBC scheme received 1,078 notifications of insured loss and 492 insurance claims.

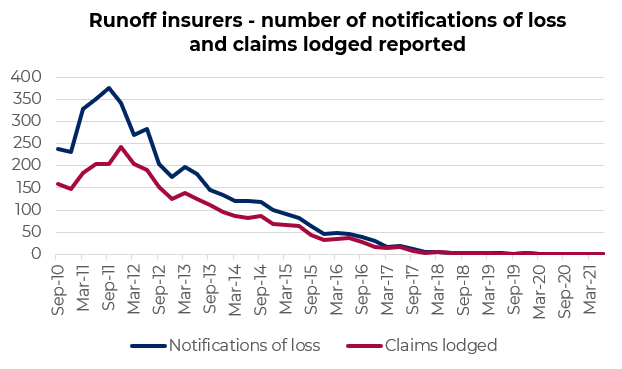

The HBC scheme is regulated by the State Insurance Regulatory Authority (SIRA). There is currently only one insurer offering insurance under the HBC scheme, the NSW Government-operated NSW Self Insurance Corporation, trading as ‘icare HBCF’. The HBC scheme was historically underfunded from July 2010 when it became government-operated, but has been the subject of reforms, premium increases and NSW Government support since 2017 to move it to a sustainable financial footing.

Private insurers which issued insurance under the HBC scheme until June 2010, continue to manage some claims on those policies.

Why we are asking for your input

In December 2020, the Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal (IPART) published the findings and recommendations of a review of the HBC scheme’s efficiency and effectiveness1. IPART suggested a range of reforms to how the HBC scheme is regulated and operated.

This paper’s purpose is to help inform the design of regulatory reforms flowing from IPART’s review. This paper also outlines some potential reforms that are additional to matters considered in IPART’s review.

What reform ideas we want your feedback about

We are seeking feedback about a range of reform ideas, a combination of which could be adopted to reform the HBC scheme. These ideas fall under three themes, being to:

- expand some aspects of the scheme to better support some homeowners;

- narrow some aspects of the scheme to lower the cost of some work on homes and reduce regulatory burdens or costs; and

- reconsider who should provide cover in the scheme and how they should be regulated.

Relationship to other building regulatory reforms

The Department of Customer Service (DCS) is concurrently reviewing the Home Building Act 1989. That review is considering a range of matters that potentially have flow-on effects to the HBC scheme, such as who is regulated under the Act, statutory warranties, regulation of building contracts and disputes remedies.

The NSW Government has also appointed a Ministerial Advisory Panel to advise on the introduction of ‘decennial liability insurance’. This would be a special type of insurance taken out by developers to guarantee against some defects for up to 10 years. It is anticipated to cover construction such as high rise multi-dwelling buildings that are not insured under the current HBC scheme.

For this reason, some matters raised in IPART’s review or otherwise relevant to the HBC scheme are not considered as part of this discussion paper. We may also adjust our advice to Government about the timing and substance of some reform ideas canvassed in this paper depending on the progress and outcomes of those concurrent review processes.

How to make a submission

We encourage you to tell us what you think about the reform ideas in this paper, or suggest alternative options. You can do this by lodging a written submission in one of the following ways:

- email to [email protected]

- the SIRA website https://www.sira.nsw.gov.au/consultations/home-building-compensation-reform

- the NSW Government Have Your Say website www.nsw.gov.au/have-your-say

Key dates

We invite you to make a submission by 16 August 2022.

Any submissions received after this date will be considered at our discretion.

Disclosure and handling of submissions

Submissions to this consultation may be published on the SIRA website.

Publication of submissions will usually include your name and the name of the organisation, if relevant. We will remove contact details such as email addresses, postal addresses and telephone numbers.

If your submission contains confidential or commercially sensitive information that you do not wish to be published, please clearly indicate in writing at the time of your submission that you prefer it or any part of it to be treated confidentially. We will then make every effort to protect that information.

At our discretion we may not publish certain submissions (or part of submissions) due to our assessment of length, content, appropriateness or confidentiality.

All personal information or health information provided in submissions is dealt with in accordance with:

- the Privacy and Personal Information Protection Act 1998 and,

- the Health Records and Information Privacy Act 2002

Any requests for access to confidential submissions are dealt with in accordance with the Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009.

What happens next

We will use the feedback we receive from this consultation, to help inform SIRA’s advice to Government about changes to the HBC scheme. We will also do further analysis or modelling where relevant to help decide which mix of reforms we recommend be implemented and their design.

We will publish further updates for stakeholders about progress and timelines during this process.

Theme 1 - Better supporting homeowners

Reform idea 1 – Cover victims of unlawfully uninsured home construction

Issue

The HBC scheme does not currently cover homeowners if a business that worked on their home unlawfully failed to take out insurance. This has resulted in some homeowners being left without help to complete or fix their home.

While available data suggests most projects are insured, there are regular examples of some unlawfully uninsured projects. This occurs despite:

- the inclusion in standard building contracts of a requirement to obtain a certificate of insurance and provide it to the homeowner,

- checks for insurance as part of certification of some types of building work, which aims to prevent uninsured work being done (e.g. work that requires planning consent such as the development of new homes)2, and

- enforcement action being taken against businesses that engage in this type of unlawful conduct, with potentially significant maximum penalties, including imprisonment, being provided in the law.3

For example, for the 2 years from 30 June 2019 to 30 June 2021, NSW Fair Trading issued 521 penalty infringement notices to building businesses for failing to insure their work under section 92 of the Act, of which, we are aware of 21 instances where homeowners were denied a claim because of uninsured loss.

The profile of people committing this type of offence range from:

- unlicensed individuals who have provided fraudulent insurance or other documents to dupe their victims into believing they are licensed and insured, to

- licensed building companies that otherwise appear to have a history of complying with their insurance obligations.

The types of projects involved range from renovation work through to the construction of homes.

There are likely to be other such instances of which we are not aware because homeowners have not attempted to make any insurance claim after discovering they had no insurance, or where there has been no building dispute that would have made it apparent that the work was not insured.

Potential reform

We want your feedback on whether we should let homeowners claim on the HBC scheme, if the business that worked on their home unlawfully failed to insure the work. We also want feedback on how we can design this option to avoid placing further pressure on insurance premiums paid by businesses that are doing the right thing by taking out insurance (and their customers who ultimately pay the cost of the insurance premiums).

The option we are considering has the following features to balance the need to protect homeowners while seeking to avoid unreasonable costs on building businesses and their customers:

- Limit scope of cover for uninsured loss: We want your feedback on limiting this option to work involved in building or altering a home that requires planning consent (i.e. work that requires a Development Application or a Complying Development Certificate) or that must be declared under the Design and Building Practitioners Act 2020. This is intended to focus cover for uninsured loss on types of work where:

- the risk of detriment to a homeowner is highest,

- there are regulatory records evidencing the work, and

- there are risk mitigations available via building certification or other regulatory action.

- Exclude owner-builder work: If adopted, we propose to exclude any work the subject of an owner-builder permit. A person who takes out an owner-builder permit is currently not able to insure work on their home themselves and they are responsible for warranties if they sell their home. They must also already include in the contract of sale for the property a ‘consumer warning’ to put the buyer on notice that uninsured work may have been done to the property

- Related entities of a building business or developer cannot claim: If adopted we propose that a person not be able to claim for uninsured loss if they are a director, shareholder or close associate of the building business or any developer of the uninsured work

- Exclude homeowners complicit in uninsured work: If adopted, we propose that homeowners not be entitled to claim for uninsured loss if there is evidence that they consented to work being done without insurance (for example, where a homeowner contracted a person they knew or should have reasonably known was unlicensed, or where there was no written contract for the work, or it was noted in the contract for the work that no insurance would be taken out)

- Obligations on claimants: If adopted, we propose that homeowners who wish to claim for an uninsured loss must have ‘diligently pursued’ the responsible business for a remedy. For example, if a problem with their home was apparent while the responsible business was still trading, they must attempt to get a remedy via NSW Fair Trading’s disputes processes or via the court or tribunal. This would be similar to obligations that already apply to claimants for insured work if they want to make a ‘delayed’ insurance claim on the HBC scheme4

- Compliance improvements to address uninsured work: We are currently leveraging technology and data sharing opportunities to better prevent or detect uninsured building work

- Recover costs from businesses and culpable directors that fail to insure work: Supported by the above improvements to detect non-compliant businesses, we are considering how we can best recover the costs of paying uninsured loss claims. In particular, we are considering whether SIRA should be entitled:

- to recover a multiple of unpaid premiums from building businesses or developers and culpable directors of corporations who are found to have failed to comply with insurance obligations under the Home Building Act (and regardless of whether there has been a claim). This could operate in a similar fashion to arrangements under the Workers Compensation scheme, which provides for SIRA to recover double the amount of unpaid insurance premiums from businesses and culpable directors of corporations, who have failed to take out insurance under that scheme5; and in addition

- to recover claim costs associated with an uninsured project from the responsible building business or developer and culpable directors.

Costs, risks, benefits and mitigations

Benefits | Quantification or detail |

|---|---|

Better protection for homeowners | Homeowners would be better protected when embarking on building or significantly altering their home, or buying a recently built or altered home. This would be achieved by improving the likelihood of work on their homes being insured, or in the event that it is not insured, ensuing the homeowner is able to access compensation to help address problems with their home. There is precedent for cover to be extended to homeowners where no insurance has been paid. Some cover was offered in NSW prior to 1997 on the proviso that the person that did the work was licensed. The equivalent Queensland insurance scheme currently provides cover if a person that contracted to do work on a home, fraudulent claimed to hold a licence under which they could contract and insure the work.6 |

Stronger incentives for compliance | For building businesses and developers (and their directors), risk of exposure to recovery of unpaid premiums and claim costs would strengthen incentives to comply with insurance obligations. |

Improved confidence in industry | This relates to increase in appetite from consumers and related parties (e.g. mortgage lenders) to be involved in a contract work on homes, knowing that there is a guarantee of help if the responsible business ceases operation and is unable to meet its obligations to the homeowner. |

Costs and risks | Quantification or mitigation |

|---|---|

Risk of pressure on insurance premiums | This risk relates to any gap between cost recovery from offending businesses that needs to be met through insurance premiums. This risk is proposed to be mitigated as described above by limiting the scope of uninsured work claims, while strengthening compliance and putting in place arrangements to recover costs from people responsible for any residual non-compliance. |

Reduced incentive for consumers to check work is insured | Home building compensation is already an insurance that most consumers have no reason to be aware of unless a business that has worked on their home ceases operation with unmet obligations to the consumer. In that context, any reduced incentive for consumers to perform checks is likely to have negligible impact on the scheme. |

Discussion questions

Question 1: Should victims of unlawfully uninsured work be able to claim on the home building compensation scheme in some circumstances? Question 2: If adopted, should cover for uninsured loss be limited to the construction or significant alteration of homes that requires planning consent or that must be declared to NSW Fair Trading? Question 3: If adopted, should homeowners be required to diligently pursue the responsible business for a remedy first, if they want to claim for uninsured loss? Question 4: Should unpaid premiums and claim costs for uninsured work be recovered from building businesses and developers that have not complied with their insurance obligations, including culpable directors? |

|---|

Reform idea 2 – Allow claims earlier in the building dispute process

Issue

One of IPART’s findings was that “building issues can be costly and take a long time to resolve through the dispute resolution mechanisms that apply when a building business is still trading.”7 The HBC scheme helps homeowners as a ‘last resort’ if they cannot use those dispute resolution mechanisms because the business that contracted work on a home has ceased to trade due to insolvency, ‘deemed insolvency’, death or disappearance. This means:

- some homeowners can experience years of legal proceedings without having their loss addressed, before some businesses cease to trade and both the loss and legal expenses and other costs incurred become part of a claim on the HBC scheme (in practical terms this may mean a consumer may be unable to use their home or part of their home, or be managing deficiencies in the home during this period, and with potential associated costs such as alternative accommodation and storage); and

- some homeowners may not get any remedy despite having a genuine problem with their home because they cannot support the time and cost that would be involved in pursuing a business through all relevant remedies and appeals.

Potential reform

We want your feedback on whether homeowners should be able to claim if the building business fails to comply with a rectification order issued by NSW Fair Trading (or an order of the tribunal or court in the event that the dispute proceeds beyond NSW Fair Trading).

This would mean a claim can be made in some circumstances where the business holds a current licence and continues to trade. This would mean that the NSW scheme would share some similarities with Queensland’s model of insurance that allows for claims if disputation processes have failed to achieve an outcome. Note however, that Queensland’s model has other distinctions from NSW, such as that it combines the role of insurer and building regulator under a single government agency: the Queensland Building and Construction Commission, which is not the model we are proposing for NSW.

We note that allowing homeowners to claim earlier in the process may better align with the proposed ‘decennial liability insurance’ for apartment buildings that is under development. We may consider further changes to this potential reform to the HBC scheme depending on the final design of the decennial liability insurance product’s claim criteria and scope. There is also a parallel review of the Home Building Act that is considering opportunities to better manage risks to homeowners and reforms to disputation arrangements. Depending on the outcome of that process we may adjust our proposed claim criteria and cost mitigations if this HBC scheme reform were adopted.

At this stage, the option we would like to test would have the following features, that are intended to balance any extension of homeowner ability to claim with reforms to limit impact on premiums:

- Allegations by a homeowner against a business must be tested: A homeowner would not be able to claim directly to the insurer, but would need to first satisfy NSW Fair Trading that there is an issue that justifies an order being made. If the order is not complied with by the due date, then homeowner would be able to claim without needing to pursue further proceedings (e.g. it would not be necessary for a homeowner to enforce an order through the court if the business failed to comply).

- Homeowners must respect orders for work: We would also expect to provide that the insurer may limit its liability for a claim if the homeowner has not allowed the insured business a reasonable opportunity to provide a remedy. Currently, homeowners already have a duty to inform the building business in writing if there is a breach of statutory warranty and allow reasonable access for the business to rectify the problem8.

- Insurers may arrange for the original or new contractor to do work: Because this option may involve claims being made where the responsible building business or developer may still be solvent, we expect an insurer would have the discretion to work with those parties to seek a remedy (for example, if a business has attempted in good faith to comply with an order, but it has not been possible to fully comply by the due date because of factors out of the business’ control).

- Remove or cap insurer liability for associated costs: Currently the HBC scheme not only helps homeowners complete or fix their home, but also compensates them for some associated losses, being: the reasonable cost of alternative accommodation, removal and storage costs, and any legal or other reasonable costs incurred by the homeowner in seeking to recover compensation from the business. If claims are able to be made early in the disputes process without proceedings in the tribunal or court, then claims costs may be able to be limited to the cost of completing or fixing a claimants home. This would more closely align to the equivalent Queensland and Victorian schemes that we understand do not cover legal costs or only in relation to appealing an insurer’s decision, and that offer less cover for other associated losses. For example, Victoria’s state insurer (VMIA) has a 60 day cap on accommodation, removal and storage costs, while Queensland’s standard insurance cover has a cap of $5,000 for accommodation.

- Shortened period in which a claim may be lodged outside the warranty period: The HBC scheme currently accepts claims up to four years after the end of the six-year statutory warranty period. This allows time for the completion of legal proceedings commenced during the warranty period, if they do not conclude until after the warranty has expired. This ‘delayed claim’ period currently means insurers are on risk for claims up to 10 years after the completion of work. If there were a faster pathway to be able to make a claim, then less time should be necessary to allow for appeals or other legal processes. Shortening the claim period reduces the period where an insurer is ‘on-risk’ for claims and must hold funds against that risk. This would also more closely align to other states or territories that do not have a ‘delayed claim’ period, such as Queensland and Victoria.

Costs, risks, benefits and mitigations

Benefits | Quantification or detail |

|---|---|

Stronger incentive for businesses to deal with disputes early | Currently building businesses do not typically need to deal with the impact of an insurance claim because the business is no longer trading when a claim occurs. Under this reform, businesses face claims while they are still trading with consequential risk of facing recovery action from insurers, loss of eligibility to insure further work, and reputational damage arising from having claims recorded against their public licence record. These may act as incentives for businesses to be more active in seeking to resolve problems with homeowners before matters are escalated to NSW Fair Trading or the tribunal or court. IPART’s analysis of similar insurance arrangements in Queensland was that even though claims can be made while a builder is still trading, most of Queensland’s claims are related to insolvency. IPART considered that claims in Queensland’s scheme are relatively infrequent for builders that are not experiencing financial issues because there are strong incentives for building businesses to rectify defects as they arise. |

More homeowners benefit from the scheme | By expanding the circumstances in which a homeowner may claim to non-compliance with rectification orders, there would likely be a larger number of homeowners who benefit from the scheme. This may also improve the perceived value of the insurance scheme as a consumer protection mechanism. In the calendar years 2019 and 2020, there were an average per year of 230 NSW Fair Trading rectification orders that were not complied with. By comparison there was an average of 578 insurance claims lodged with icare HBCF per year in the same period. However, this may not reflect the potential increase in claims because some non-complied orders may relate to matters that ultimately become claims under the current scheme, and the number may not include matters that proceeded to tribunal or court disputation without an order from NSW Fair Trading having been made. |

Potential reduction in insurance premiums | IPART observed that claims costs are significantly lower under the Queensland scheme compared to NSW – leading to lower premiums. Balancing increased claims with other measures to reduce pressure on the scheme may achieve a similar outcome in NSW, but will depend on the design of the model adopted and successful implementation. |

Faster outcomes for homeowners | Homeowners would no longer need to exhaust their remedies against a business in order to make a claim on the scheme. Evidencing to the satisfaction of NSW Fair Trading (or the tribunal or court) that they have a problem warranting the issue of an order against the business would be sufficient to justify a claim. For some homeowners this would mean a much faster pathway to getting a remedy, potentially avoiding up to years of time and cost spent on litigation. |

Increased customer confidence in the building industry | Greater certainty that consumer protection will be accessible, would be likely to improve consumer confidence to enter into contracts with businesses to build or renovate a home. |

Greater likelihood of insurer to recover claim costs | Currently claims are typically made where the business responsible for a loss is no longer trading, so there is limited or no ability to recover from that business any claim costs. If claims are allowed against businesses that are still trading, there may be more capacity for insurers to take recovery action against the business while it is still trading. |

Costs and risks | Quantification and mitigation |

|---|---|

Risk of disagreements between insurers and Fair Trading | If non-compliance with an order of NSW Fair Trading becomes a circumstance where insurers become liable for homeowner claims, this may place increased pressure on NSW Fair Trading’s disputes processes, and risks instances of insurer disagreement with the regulator. This may be mitigated by strengthened regulation and oversight of building work through the NSW Government’s reforms to apartment building regulation and the review of the Home Building Act. |

Risk of disagreements between insurers and building businesses | Currently the scheme only pays out a claim if the responsible business is no longer available to respond. This means that the business also cannot dispute the claims decisions and management of the scheme’s current sole insurer. If claims can be made against businesses that are still trading, there is more scope for disagreement between insurers and their building industry customers (and reputational risk to Government as a scheme regulator and operator). However, if the claims experience of Queensland is replicated in NSW that would imply the majority of claims will still relate to insolvent businesses. The risk may also be mitigated by permitting insurers the discretion to make further attempts to resolve the problem with the original building business. |

Risk of increased claim costs and premiums | Making it easier for homeowners to claim, risks exposing the scheme to a larger number of claims. IPART engaged actuarial consultants to consider the costs and benefit of introducing a Queensland-style scheme in NSW. That analysis considered several different scenarios, based on the claims experience in Queensland, and which could result in a reduction or increase in premiums. A risk of increased premiums may be mitigated (or premium reductions achieved) by the reform also having the effect of reducing some insured losses and by reforms to reduce the period allowed for claims and limit the scheme’s liability for associated costs. There is also significant work underway to improve the ‘upstream’ regulatory system that may reduce underlying risk of homeowner losses, and thus reduce costs of the insurance scheme. For example, the NSW Government has implemented significant reforms to how it regulates apartment building construction to reduce risks to homeowners. |

Risk insurers will be drawn into legal disputes with building businesses. | Claims may be made to the insurer before appeals processes are exhausted, and insurers would likely be drawn into some appeals processes (e.g. some claims may be awarded to homeowners where the insured builder is ultimately found to not be responsible for the loss on appeal). An insurer may be left with some losses they cannot practically recover from either party in such circumstances. |

Discussion questions

Question 5: Should homeowners be able to make an insurance claim if the business that worked on their home fails to comply with a rectification order issued by NSW Fair Trading (whereas currently claims are only accepted if the business is no longer trading)? Question 6: If homeowners are provided a quicker pathway to claim, should claims be limited to losses directly arising from non-completion and breaches of statutory warranty (i.e. remove cover for associated losses such as legal costs or alternative accommodation, removal and storage costs). Question 7: If homeowners are provided a quicker pathway to claim, should claims be limited to those lodged within the 6-year warranty period, plus an extended 6 months for losses that only became apparent at end of the warranty period (whereas currently the scheme accepts claims up to 10 years after the work is completed)? |

|---|

Reform idea 3 – Update the minimum insurance cover

Issue

The minimum amount of cover insurers must offer under a contract of insurance has not changed in ten years. It is currently $340,000. In practice, this is the maximum a person may claim, because icare HBCF does not offer contracts of insurance that provide more than that minimum amount of cover.

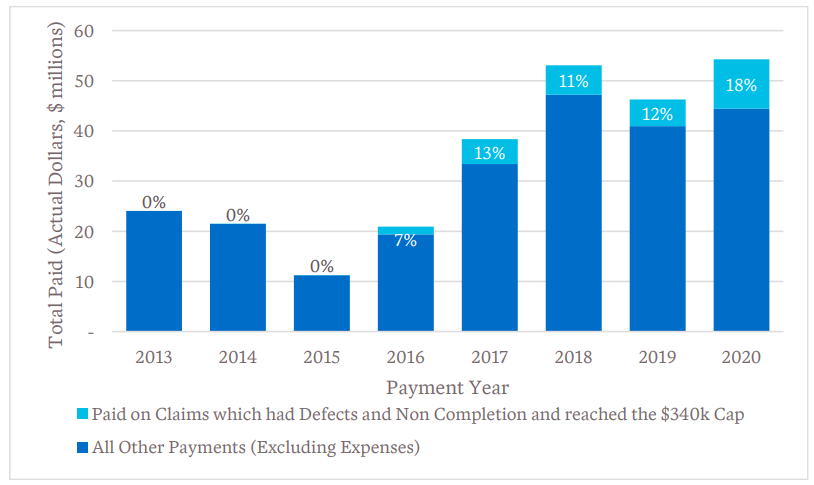

Analysis published by IPART9 suggests that, since a previous review of the scheme in 2015, there has been an increasing number of claims that have reached or exceeded the current minimum cover of $340,000, as shown in the following chart.

Chart 1: IPART analysis of historic claim payments which have multiple claim types and have been capped

Government statistics and industry data also indicate significant recent increases in the cost of building work. For example, for the year ending March 2022, the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that in NSW there was a 13.5% increase in house construction prices and a 9.5% increase in other residential construction prices10, while CoreLogic’s Cordell Construction Cost Index indicated national construction costs increased 9% over the 12 months to March 202211.

Potential reform

We want your feedback about what should be the minimum cover offered by the scheme to reflect changes in the cost of building work, and how often this amount should be updated. There is currently no set frequency for updating the insured amount, with the most recent changes having occurred in 1997, 2007 and 2012.

Table 1 Historical changes in minimum insurance cover since 1997:

Time period | Minimum level of insurance cover |

|---|---|

1 May 1997 to 28 February 2007 | $200,000 |

1 March 2007 to 31 January 2012 | $300,000 |

1 February 2012 to present | $340,000 |

One way to consider adequacy of the minimum insured amount is to consider whether it is reflective of changes to the typical value of new home construction. The minimum insured amount is particularly relevant to these types of projects because they are most likely to involve higher valued work or claims. SIRA data outlined below shows that average construction costs for new dwellings insured under the HBC scheme have increased since financial year 2012-13 to between $263,000 and $399,000 depending on the type of building. On this basis we have suggested the insured amount be adjusted to $400,000.

Table 2: Comparison of new dwelling work value for financial years 2012-13 and 2020-21

Average value of contracted work | C01 New single dwelling | C09 New duplex, triplex etc | C03 New multi dwelling (3 storeys or less) | Total new dwelling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

FY 2012-13 | $308k | N/A | $205k | $284k |

FY 2020-21 | $399k | $316k | $263k | $369k |

A further consideration is that the legislation currently allows for different minimum insured amounts to be prescribed depending on whether work is:

- insured under a single contract of insurance (which is the only option currently offered by the sole insurer icare HBCF); or

- insured under two contracts of insurance (‘split cover’), one covering the construction period, and the other covering the post-completion warranty period.

Currently the $340,000 amount is prescribed for the single insurance contract, and for each of the ‘split cover’ insurances if any were to be offered. We want your feedback whether any updated figure should similarly apply to all insurance contracts, or whether there should be a different amount of cover for ‘split cover’ contracts.

Some stakeholders suggested that, instead of prescribing a fixed minimum cover amount, the insurance should offer cover equal to the value of the insured work. For example, a $30,000 renovation project would have only $30,000 of cover, while a $500,000 project to build a home would offer $500,000 (similar to how the cover offered by ‘sum-insured’ home insurances may vary depending on the estimated cost of rebuilding insured homes).

We have considered, but rejected this option because:

- the benefits to homeowners are confined to those with building projects over $340,000, while reducing the cover available in other cases,

- it relies on the business contracting the insurance to accurately report the value of the work, and any variations, as the basis for the amount of cover the insurance will provide, (and in the context that there are perverse incentives to underreport that value to reduce the insurance premium the business must pay, while risking homeowners being left with inadequate insurance cover), and

- there may not be reliable documentation available to verify construction values to mitigate that risk

Costs, risks, benefits and mitigations

Benefits | Quantification or detail |

|---|---|

Minimum insurance cover reflects typical building costs | Adjusting the insured amount would increase the likelihood of homeowners being able to recover reasonable losses, while continuing to cap the scheme’s total liabilities. |

Greater certainty for industry or homeowners about timing of indexation | Providing a legislative or administrative commitment to how often the insured amount will be reviewed would provide greater predictability and certainty for all stakeholders about the timing of future reviews and adjustments. |

Costs and risks | Quantification or mitigation |

|---|---|

Risk of higher scheme liabilities and premiums | An increase in the insured amount will only affect a minority of claims where there is a loss of between $340,000 and $400,000, which would not be covered under the current scheme’s limits. This would need to be factored into future premium rates together with any other reductions or increases in scheme costs arising from any reforms adopted from this discussion paper. That impact has not been estimated at this point. |

Discussion questions

Question 8: Should the minimum amount of cover offered by the scheme be increased from $340,000 to $400,000 to reflect the increase in the average cost of building a new single dwelling since the cover amount was last updated in 2012? If you prefer a different amount, please tell us what it is and your reasons. Question 9: The legislation allows for projects to be insured by means of two contracts of insurance (one covering the construction period and the other for the post-completion warranty period), although no insurer offers this option at this time. If insurers were to start offering this option, should each contract also be increased from $340,000 to $400,000 of cover (i.e. together offering a potential total of $800,000 cover)? If you prefer a different amount, please tell us what it is and your reasons. Question 10: How often should the threshold amount be reviewed: a) every 3 years? b) every 5 years? c) every 10 years? If you prefer a different frequency, please tell us what it is and your reasons. |

|---|

Reform idea 4 – Increase cover for non-completion claims

Under the HBC scheme, insurers are not required to cover losses arising from non-completion of work that exceed 20% of the total contract price for the building work. However, claims data indicates that the majority of non-completion claims involve losses that have reached or exceeded that 20% amount.

Progress payment reforms to the Home Building Act that made in 2015 were intended to help limit homeowner risk of overpaying for work not yet complete on a project. Claims data suggests that this has not reduced the proportion of insurance claimants whose losses have exceeded 20%.

Table 3 – Claims to icare HBCF for non-completion that have been capped

Year claims reported | Total number of non-completion claims | Number of non-completion claims that have reached the 20% cap | Percentage of non-completion claims that have reached the 20% cap |

|---|---|---|---|

2011 | 82 | 30 | 37% |

2012 | 250 | 160 | 64% |

2013 | 208 | 142 | 68% |

2014 | 34 | 19 | 56% |

2015 | 128 | 60 | 47% |

2016 | 215 | 128 | 60% |

2017 | 117 | 67 | 57% |

2018 | 149 | 78 | 52% |

2019 | 183 | 92 | 50% |

2020 | 187 | 121 | 65% |

Potential reform

We want your feedback about whether we should increase the amount of cover that the scheme provides for non-completion claims to address this issue. We expect that increasing any amount of cover would potentially have an impact on the premiums, for example:

- if cover for non-completion claims were increased to 25% of the value of the insured work, this is estimated to require a 2.4% increase in premiums, or

- if cover for non-completion claims were increased to 30% of the value of the insured work, this is estimated to require a 4.9% increase in premiums.

Costs, risks, benefits and mitigations

Benefits | Quantification or detail |

|---|---|

Better consumer protection | Increasing the cover for non-completion claims would benefit the majority of homeowners who make that type of claim, who currently reach or exceed the current cover amount (an average 56% of such claimants). |

Costs and risks | Quantification or mitigation |

|---|---|

Increased premiums | If this reform were adopted, it is expected to require an increase in the cost of insurance to pay for the increase in cover. Overall impact on the premiums is expected to be an additional 2.4% to 4.9% depending upon the cover offered. |

Discussion questions

Question 11: Should the cover for non-completion claims be increased from 20% of the value of the insured work, given most non-completion claims exceed that amount? Which of the following options do you prefer?

|

|---|

Reform idea 5 - Publish exemptions granted by SIRA

Issue

SIRA can currently exempt a person (e.g. a building business or developer) from insurance requirements in a particular case, if there are special circumstances or if full compliance is impossible or would cause undue hardship. There is currently no public register on which a person with an interest in a property may check whether work on the property was done without insurance on the basis of an exemption granted by SIRA (for example a person considering buying a property). SIRA currently publishes only general information in its annual report about exemptions it has granted. In 2019-20, SIRA determined six applications for insurance exemptions, of which four were approved and two were refused.12

Potential reform

We want your feedback about whether SIRA should be required to publish details of insurance exemptions that SIRA has granted. Details may include the property address, reason for the exemption, nature of the work, and the identity of the person who was granted an exemption (e.g. the name and licence number of a building business).

Publication of this information could be done in a number of ways. Given the relatively small number of exemptions granted each year, this could be a simple list published on SIRA’s website or could done by including these records in SIRA’s existing public register of insurance (www.hbccheck.nsw.gov.au).

Costs, risks, benefits and mitigations

Benefits | Quantification or detail |

|---|---|

Open, transparent data | Parties with an interest in a property (e.g. banks, property buyers) would be able to easily check if uninsured work done to a property was done lawfully under an exemption granted by SIRA. |

Increased accountability for SIRA and exemption applicants | SIRA’s responsibility for determining applications, activity and the rationale for decisions to grant exemptions would be more transparent. Applicants would be accountable for providing correct information and agreeing to publishing certain details on the register as part of applying for an exemption. |

Costs and risks | Quantification or mitigation |

|---|---|

No material costs or risks identified | Given the small number of exemptions granted each year there is unlikely to be a material cost to publishing information about them. SIRA already publishes details of all projects that are insured in a public register and could publish a similar scope of matter about exempted projects. SIRA may need to adjust its exemption application procedures to ensure applicants are aware that details of an exemption will be published if granted. |

Discussion questions

Question 12: Should SIRA publish a register of projects that SIRA has exempted from insurance, so that a person with an interest in the property may check whether work was lawfully done without insurance under an exemption granted by SIRA? |

|---|

Theme 2 – Housing affordability and regulatory burdens

Reform idea 6 – Update the threshold for requiring insurance

Issue

The Act requires building businesses to obtain insurance for residential building work if the contract price is more than $20,000 including GST, unless exempt.13 If the contract price is not known, insurance is required when the reasonable market cost of labour and materials to be supplied by the business exceeds $20,000. The threshold amount of $20,000 has not changed since 2012. It was last reviewed in 2015-16, but not amended at that time.

As noted under reform idea 3, data from within the insurance scheme as well as other statistics support the view that the cost of doing building work has increased over the last decade. This inflation means that the threshold for where insurance is required has reduced in real terms since it was last adjusted. This has the practical effect that the size of projects that can be done without insurance has been shrinking. It means more businesses and their customers need to pay for the cost of insurance.

Potential reform

We want your feedback about whether the $20,000 threshold above which insurance is required should be adjusted, and if so what the new amount should be. We also want your feedback on how often the threshold should be reviewed. In doing so, we note:

- Since financial year 2012-13 the average value of insured work has increased by 27%, which would equate to an increase in the threshold to $26,000 (with rounding up).

- NSW (together with Western Australia) already has the equal highest threshold for requiring insurance at $20,000. Other jurisdictions have thresholds ranging from $3,300 to $16,000.

- The current insurance threshold aligns to the current $20,000 threshold above which businesses must comply with certain detailed contract requirements under the Home Building Act 1989 (and that Act is currently being reviewed).

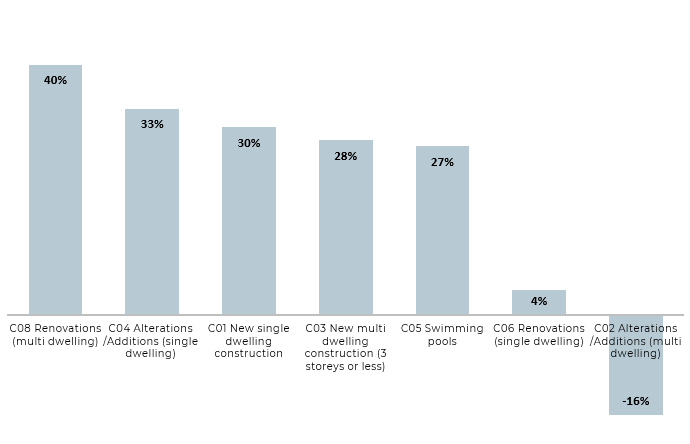

Scheme data outlined in the chart below shows the average value of insured work has increased across all but one type of work that is insured under the scheme.

Chart 2: Change in average value of insured work by construction types between FY 2012–13 and FY 2020-2

Note: for construction of ‘C09 new duplex, triplex etc’ data is only available from FY 2014-15 and shows a 38% increase.

Table 4: Jurisdictional comparative table for insurance thresholds

NSW | QLD | VIC | ACT | SA | Tas | WA | NT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

$20,000 | $3,300 | $16,000 | $12,000 | $12,000 | N/A | $20,000 | $12,000 |

Costs, risks, benefits and mitigations

Benefits | Quantification or detail |

|---|---|

Cost saving for businesses and homeowners | Builders undertaking low value projects would no longer be required to apply for eligibility for insurance or purchase insurance. This also means these costs are not passed on to homeowners for such projects. |

Larger pool of businesses able to do low value work | Homeowners have greater choice over which businesses they contract to do smaller projects on their home because they are not limited to those eligible for insurance. |

Costs and risks | Quantification or mitigation |

|---|---|

Consumers of lower cost projects are not insured | The scope of work requiring insurance has been growing in real terms due to inflation since 2012. To the extent that adjusting the insurance threshold reflects this, it is simply restoring the threshold in real terms to the scope of work that was required to be insured in 2012. |

Smaller premium pool over which to spread claims | Increasing the threshold would narrow the scope of work needing insurance, meaning the insured risk would be spread over few projects. However, if the threshold were increased by $6,000 in line with the average increase in build costs, then this impact is unlikely to be significant as it simply seeks to reflect building cost inflation since the threshold was last adjusted. |

Discussion questions

Question 13: Should the $20,000 threshold above which work must be insured be increased to $26,000 in line with increases in the average cost of building since the threshold was last updated in 2012? If not, what should the threshold be? Question 14: How often should the threshold amount be reviewed: a) every 3 years? If you prefer a different frequency, please tell us what it is and your reasons. |

|---|

Reform idea 7 – Opt-outs or premium caps for high value projects

Issue

Building businesses (and ultimately their customers) pay premiums that are calculated, in part, based on the value of the insured work. This can result in high premiums for high value work in comparison to the fixed amount of compensation the homeowner may claim under the scheme. Insurers under the scheme are not obliged to offer more than $340,000 of cover per dwelling. There are also other additional limits to liability that apply within that $340,000 amount. Insurers are only obliged to cover 10% of the value of the work for loss of deposit if work has not commenced, and 20% of the value of the work for loss arising from incomplete work. IPART found that depending on the homeowner’s risk appetite, this may present poor value for money.

Where claims do occur for work on single dwellings of $2 million or more, most approach or hit the cap of $340,000, which suggests the homeowners are more likely to suffer uninsured losses exceeding that amount.

IPART recommended that the insurance requirement be made voluntary for high-value single dwellings. IPART suggested this apply to work over $2 million, noting that for work of that value, a 20% non-completion claim would exceed the cover offered under the scheme (this would continue to be true even if the insured amount were increased to $400,000 under option 3 above). IPART suggested homeowners be given the choice whether to buy insurance in such circumstances or use the premium they save to manage their risk in other ways. This would also mean accepting that if a home on which uninsured work were done were sold during the warranty period, the new owner would not have the benefit of the insurance.

Potential reform

We want your feedback on whether homeowners and the businesses they contract with should be able to agree to opt-out of insurance for work over $2 million done to construct, alter or renovate a single dwelling. The option we want your feedback on would have the following features:

- The insurance opt-out must be included in the contract for the work: Where the parties to a contract intend to opt-out of insurance, they would need to specify this in the contract for the work. This would ensure that there is a written record that the parties consent, and that may provide a documentary basis to satisfy for certification or other purposes that the project may be lawfully done without insurance. The proposal is similar to the existing model that is already used to allow public sector agencies to opt-out of insurance when contracting residential building work14. We expect that a person who is able to afford to do $2 million of work on their home is able to seek suitable legal advice and make an informed decision in these circumstances.

- The opt-out would be based on the initial value of the construction contract:

- We propose that if this option were adopted, then the threshold would apply to the initial contracted value of the work, and regardless of any later variations to the contract:

- If a project were contracted for more than $2 million and opted-out of insurance, but later varied during construction to below that amount, it would not be practical to require partially-completed project to be insured. This is because there may not be any insurer willing to insure the business or the project at that point.

- Equally we do not intend to provide for retrospective cancellation of insurance and premium refunds in the event that, at the start of a project, it is for less than $2 million, but during construction a variation results in the total value of the work becoming higher than $2 million. This present unnecessary complexity and cost burden on insurers who have already incurred costs in writing a policy for the project.

- The $2 million threshold would be set by regulation: If adopted, we propose that the opt-out amount be prescribed by regulation so that it may be reviewed and updated periodically. We expect it would be reviewed with the same frequency as the minimum insured amount, and cost threshold for work above which insurance is required (see reform ideas 3 and 6).

- No contract-of-sale disclosure or reporting obligations: Due to the risk to some home buyers of purchasing a home that has uninsured, high value works, we have considered whether this should be mitigated by means of requiring disclosure of the uninsured works in the contract of sale, and/or making a condition of any ‘opt-out’ that the work must be reported to SIRA so that it may be published in a public register. We have rejected these measures on the basis that:

- it is not a proportionate response to the relatively few homes likely to be affected;

- the consumers involved must have significant resources available to buy such homes, and are likely to be able to seek relevant professional advice before buying such a home and can manage their own risk without the relatively modest assistance of the insurance scheme compared to the value of the homes concerned; and

- compliance with contracts-of-sale disclosure requirements cannot be readily monitored and enforced because SIRA is not privy to the content of contracts-of-sale.

Alternative options we have considered

- Capping premiums for high value work: A viable alternative to an opt-out for high value work, is to instead place an upper limit on the amount of premium that may be charged for such projects. For example, this could be done by providing that the premium may be calculated based on the value of the construction up to a specified value (e.g. $2 million). This would ensure premium costs do not become disproportionate to the cover offered under the scheme.

- Optional additional cover for high value projects: We have considered and rejected an option to instead require insurers to offer homeowners that are contracting high value works the option to pay for an additional amount of cover. Experience with an existing ‘optional additional cover’ model under the equivalent Queensland scheme has been that very few consumers have taken out that option15. In any case, reforms to the NSW scheme that commenced in 2018 already ensure that such a model could be offered on a voluntary basis by insurers if they considered this would be commercially viable and attractive to consumers.

Costs, risks, benefits and mitigations

Benefits | Quantification or detail |

|---|---|

Financial saving for homeowners | The base premium rate to build a single dwelling (inclusive of GST and stamp duty) is 1.003%. This implies a saving for the building business and homeowner of more than $20,000 of avoided premium for each project over $2 million that is ‘opted-out’. This benefit is likely to be partially offset by smaller increases to premiums for other projects that remain in the scheme. In the alternative that premiums for high value projects are capped rather than allowed to opt-out of insurance, there is a smaller saving in premium costs for such projects, but also likely to be less impact on premiums for lower value projects that stay within the scheme. |

Avoided insurance eligibility costs for businesses that specialise in high value work | In addition to the above avoided premiums, building businesses that specialise in high value home construction and alteration may achieve further savings by no longer needing to apply for insurance eligibility or to satisfy eligibility criteria, which would otherwise place burdens on how they choose to run their business. |

Increased choice of contractors for homeowners | Currently homeowners can only contract a business that meets the sole government insurer’s eligibility requirements. If homeowners can opt-out of insurance, they would be able to engage a more diverse range of contractors to work on their home. For example, a homeowner could contract a licensed builder that works in commercial or high-rise apartment construction that does not hold insurance eligibility. |

Costs and risks | Quantification or mitigation |

|---|---|

Smaller premium pool over which to spread claims | Currently, premiums collected from high value contracts have a net positive impact on the scheme. However, removing these is not expected to have a significant effect at a scheme level because very few projects are insured for over $2 million of work on single dwellings. They make up only 0.2% of the overall home building market and 0.48% of the single dwellings market (based on data for the period between July 2018 and June 2020). icare HBCF has offered a preliminary view that the impact could be under $7 million per year of premium forgone. In the alternative that premiums were capped for high value projects instead, icare HBCF estimates that reduces the impact by $3 million. |

Incentive for dishonest contracting behaviours to avoid insurance obligations | There is a risk of some projects being initially contracted above $2 million to avoid insurance costs with an understanding between the business and customer that the amount will later be varied to below this figure. We consider this risk is most likely where work is already close in genuine value to the $2 million threshold, so it is unlikely to be a material risk to adopting this reform option. |

Risk of uninsured loss for some homeowners | There is a risk that in the absence of insurance some homeowners may be left with an uninsured loss, either from contracting with a business that ceases to operate or buying a home to which uninsured work was done. This risk is mitigated by the small number of projects concerned, and the fact that such homeowners are likely to have the financial means to make an informed decision, and to manage any resulting loss themselves. |

Discussion questions

Question 15: Should homeowners and building businesses be able to agree to opt-out of insurance for work of over $2 million to a single dwelling? Question 16: Alternatively, should insurance remain mandatory for high value work on single dwellings, but with premium prices be capped for work over $2 million? |

|---|

Reform idea 8 – Broader insurance exemptions for high rise buildings

Issue

IPART’s review noted some stakeholders think there is a lack of clarity over whether insurance is required for renovations and alterations done in multi-dwelling buildings over three storeys high. In general terms, a building business or a developer is exempt from HBC insurance obligations under the Act for residential building work relating to the construction of a multi-dwelling building over three storeys high, i.e. the work:

- must involve the construction of a dwelling, and

- the final result must be a building with more than three storeys and that contains two or more separate dwellings.

In other cases, work such as renovation and alteration of buildings must be insured regardless of the number of storeys (such as residential building work over $20,000 involved in internally renovating a single strata lot or work to repair and maintain the common property of a high-rise strata building).

Because there are different requirements depending on the type of work being done to a building over three storeys:

- a business will not need HBC insurance to construct a whole high-rise residential building, but will need insurance if contracting some types of work on an existing high-rise residential building,

- some businesses may unwittingly break the law and be exposed to penalties for failing to take out insurance because they do not realise they must have insurance for a renovation or alteration projects,

- owners corporations of high rise residential strata buildings can have less choice over which businesses they can ask to work on their building (because only contractors eligible to obtain insurance can do the work) and face higher costs for the work due to the added cost of insurance,

- it may be difficult for businesses to determine whether particular types of projects must be insured or alternatively will be subject to the strata building bond scheme (for example, where an existing building is being converted for residential use, or there is work to an existing building that involves a change to the number of dwellings, or the building is being partially demolished and rebuilt).

To address stakeholder concerns, IPART recommended that SIRA provide more guidance for the building industry that addresses whether insurance is required for alterations and renovations for multi-units above three storeys.

Potential reform

We would like your feedback about whether it would be better to adopt a broader and clearer insurance exemption, i.e. to expand the current insurance exemption so that all work on a new or existing multi-dwelling building over 3 storeys would not require insurance. This would align to the approach that is already in place in most other States and Territories. Currently NSW, Victoria and South Australia are the only jurisdictions that require insurance for work on existing buildings over three storeys.

Table 5: Inter-jurisdictional analysis of insurance requirements for multi-dwelling buildings more than 3 storeys high

State / Territory | NSW | QLD | VIC | SA | WA | ACT | NT | TAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Construction of multi-dwelling buildings | Not insured | Not insured | Not insured | Not insured | Not insured | Not insured | Not insured | N/A – statutory insurance scheme yet to be introduced |

Renovations or alterations / additions in multi-dwelling buildings | Requires insurance | Not insured | Requires insurance | Requires insurance (if development approval is required) | Not insured | Not insured | Not insured | N/A - as above |

Costs, risks, benefits and mitigations

Benefits | Quantification or detail |

|---|---|

Reduced premium costs for owners and building businesses | The base premium rate for multi dwelling alterations or renovations including GST and stamp duty are 7.630% and 2.361% respectively of the value of the work. For FY 2020-21: 7,383 certificates of insurance were issued for the renovation or alteration of multi-dwelling buildings with total insurance premiums of $15.1 million. This implies a saving on insurance costs of, on average, approximately $2,000 per insurance certificate for each renovation or alteration project that no longer requires insurance (some certificates will be for a whole project, and some will be per dwelling for a project). |

Wider choice for businesses and owners | Businesses would not need to apply for insurance eligibility from icare to be able to contract work that is exempt from insurance. This also means owners may have a wider choice of who they want to contract to work on their building. |

Reduced risk of noncompliance with insurance or strata bond obligations | Simplifying insurance obligations would be likely to reduce the risk of a building business or developer inadvertently failing to comply with a requirement to take out insurance or lodge a strata building bond. |

Reduced costs to business to determine requirements | Where the legal obligations of businesses are unclear they may currently incur costs involved in seeking legal or technical advice or holding costs if work is delayed. |

Costs and risks | Quantification or mitigation |

|---|---|

Risk of uninsured losses | While owners corporations may achieve lower cost to have work done from removing insurance requirements, the flip side of this is that owners corporations will no longer have the benefit of insurance cover for exempted work. This risk is mitigated in part by improvements in the regulation of work on apartment buildings being led by the NSW Building Commissioner, which should reduce the risk of defective work occurring. It may also be mitigated by some exempt work instead being subject to the strata building bond scheme (if the work is being done for the purposes of, or contemporaneously with, the registration of a strata plan or a strata plan of subdivision of a development lot)16. |

Smaller premium pool over which to spread claims | Exempting work from insurance will have the consequence of narrowing the premium pool over which risk is spread. The impact is uncertain because scheme data is not reported based on the number of storeys in a building, and in some cases work on an individual strata lot that does not include common property may be grouped with data about renovations to single dwellings such as houses. |

Discussion questions

Question 17: Should the insurance exemption for the construction of multi-dwelling buildings over 3 storeys be expanded so that insurance is not required for renovations or alterations to such buildings? |

|---|

Reform idea 9 – Insurance exemptions for some housing services

Issue

Policies of insurance must be bought, but have no beneficiary, for the development of some social or affordable housing or specialist disability accommodation. In this scenario the insurance is an added cost for the build and upkeep of such housing, which offers no benefit to any person. This occurs because the HBC scheme is not required to insure developers, so where a developer does not sell the homes, but retains ownership to provide long term housing services, there is no person able to claim on the insurance.

A principle that insurance should not be payable where there will be no beneficiary is already reflected in a range of prescribed circumstances where there is an automatic exemption from insurance or from the Act, or where the parties to a contract may opt-out of insurance. For example, the law already provides:

- an insurance exemption for work done on behalf of operators of retirement villages that are not subject to a community land scheme, company title scheme or strata scheme17;

- an insurance opt-out for work done on behalf of a public sector agency, whereby the agency and the building business can ‘contract out’ of insurance requirements,

- insurance is not required for work on some types of housing that are excluded from the definition of a ‘dwelling’ under the Act, such as guest houses, hostels or residential parts of health care buildings or educational institutions.

The Act also allows for developers or building businesses to apply to SIRA for an exemption in a particular case if there are exceptional circumstances. In 2019-20, SIRA determined six applications for insurance exemptions, of which four were approved and two were refused. SIRA has granted exemptions where a number of factors together support that there would not be a beneficiary if the project were insured, such as where a combination of the following factors exists:

- the work requires development consent and the conditions of the consent require the homes to be used for housing services,

- the project is supported by Government funding that requires the homes to be used for housing services for a period of time that will exceed the period of insurance,

- the project is being done on behalf of a charity registered with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission, and/or

- the project is being done on behalf of a Community Housing Provider registered under the National Regulatory System for Community Housing, or a specialist disability accommodation provider registered with the National Disability Insurance Scheme and the contract for the work requires that the homes must be built to the SDA Design Standard.

Potential reform

We want your feedback on whether we should automatically exempt from insurance, work done for the purpose of social and affordable housing, and self-contained specialist disability accommodation.

While proponents of such projects can apply to SIRA for an exemption in a particular case, this process can be costly and time consuming for the applicant. In practice, very few applications are made. The Act does not define what ‘exceptional circumstances’ means, so each application must be considered in detail on its individual merits and there is a high burden of information that must be provided to SIRA. Applicants typically provide documents ranging development consents, proof of property ownership, building contracts, plans, funding arrangements, and agreements that will be entered into with service recipients. It can also take an extended time to supply all necessary documentation together with SIRA reviewing it and providing a determination. For the applicant this means administrative burden, potential costs involved in seeking legal or other advice, and holding costs if commencement of work is delayed, and which may also mean a delay in the provision of housing services to customers.

We also want your feedback about what should be the criteria for such an insurance exemption. We suggest that work be exempt from insurance where the following criteria exist:

- the parties to the contract for the residential building work include a charity registered with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission, that is:

- a Community Housing Provider registered under the National Regulatory System for Community Housing, or

- a Specialist Disability Accommodation provider registered with the National Disability Insurance Scheme; AND

- the circumstances of the work include one or more of the criteria that:

- the development consent for the work to be done must include a condition that the dwellings must be used for the purposes of social or affordable rental housing, or specialist disability accommodation,

- the complying development certificate for the work to be done must include a condition that the dwellings must be used for the purposes of social or affordable rental housing, or specialist disability accommodation, or

- there is a restriction on the use of land for social or affordable rental housing, or specialist disability accommodation on the title of the land.

We have chosen these criteria, because they rely on factual, publicly available information, and mitigate the risk of uninsured homes being on-sold to consumers

Costs, risks, benefits and mitigations

Benefits | Quantification or detail |

|---|---|

Reduced costs to develop social or affordable housing and specialist disability accommodation | Based on scheme data for FY2020-21, we would expect an average saving of approximately $11,017 per dwelling for building new homes, and approximately $4,839 for each renovation or alteration project that no longer requires insurance. In addition, we assume at least 4 projects per year will avoid the costs of applying to SIRA for an insurance exemption. |

Costs and risks | Quantification or mitigation |

|---|---|

Risk of uninsured loss if homes are sold | This risk is mitigated by the criteria we have suggested that would limit the insurance exemption to work where there is a high degree of certainty that the properties will not be sold, and there is not profit-motive to do so. |

Discussion questions

Question 18: Should building work be exempt from insurance if there will be no beneficiary, because the homes will be used to provide social or affordable housing or specialist disability accommodation? Question 19: Should this insurance exemption be limited to building work done on behalf of charities that provide housing services, so that there is no profit motive to sell the homes without insurance? Question 20: Should this insurance exemption only apply to work where the conditions of planning consent or restrictions on the use of the land require that the homes must be used for housing services? |

|---|

Reform idea 10 – Insurance exemptions for local government

Issue

In 2021, the NSW Government released a whole-of-government housing strategy called ‘Housing 2041’.18 Under the strategy, the NSW Government intends to support the use of council-owned land for housing, where this is deemed appropriate by local communities. Insurance is arguably an added and unnecessary cost for local government to develop its own land for housing purposes because:

- if the council retains ownership of the property to provide housing services there can be no insurance beneficiary because the scheme is not required to insure developers (i.e. council would not be able to claim on the insurance); or

- if the homes were to be sold, the council, as a developer, will have statutory warranty obligations to the purchasers regardless of whether the work were insured.

Potential Reform

Currently, public sector agencies of the NSW Government are automatically exempt from insurance requirements if they do residential building work. They are also able to opt-out of insurance when contracting building businesses to do work on their behalf.19 This exemption does not currently apply to councils.

We want your feedback about whether we should extend the exemption arrangements to councils, in circumstances where council acts as a developer.

Costs, risks, benefits and mitigations

Benefits | Quantification or detail |

|---|---|

Reduction in regulatory burden | An exemption from HBC insurance can materially reduce the cost for local government to take up the role of developing housing. Currently the base insurance premium to develop multi-dwelling housing ranges from 5% of the cost of the building work in regional NSW to 6.250% in metropolitan locations. |

Costs and risks | Quantification or mitigation |

|---|---|

None identified | N/A |

Discussion questions

Question 21: Should councils be exempt from insurance to develop housing on council-owned land? |

|---|

Reform idea 11 – Premium refunds or exemptions for ‘build-to-rent’ schemes

Issue

Build-to-rent (BTR) properties are a new type of housing model for NSW, where a developer retains ownership of a residential building and offers homes for long term lease. Developers are not required to be beneficiaries under the insurance scheme. This means for such developments there will be no beneficiary who could claim on the insurance for work on a BTR property, despite it being a legal requirement that insurance must be purchased.

The NSW Government has adopted a policy to encourage large scale BTR developments by offering certain tax concessions to BTR developments that contain at least 50 self-contained dwellings. In this context, the insurance is arguably an unnecessary cost, that works against the NSW Government’s policy to encourage this type of housing.

This is not an issue for the construction of developments over 3 storeys high, because that type of construction is already exempt from insurance. However, insurance costs would currently apply to the construction of a BTR development that is up to 3 storeys high, and also the renovation or alteration of any BTR property regardless of the number of storeys.

NSW Government policies20 to encourage BTR provide that eligible BTR properties will receive a 50 per cent reduction in land value for land tax purposes21. The effect of this is that land tax will be reduced. BTR developments will also receive an exemption from foreign investor duty and land tax surcharges (or a refund of surcharges paid). BTR properties must satisfy the requirements specified in the Treasurer’s guidelines22 which includes that a BTR property must contain at least 50 self-contained dwellings that will be used specifically for the purpose of BTR. Developers that subdivide within 15 years of receiving the concessions will be required to repay the benefit.

Potential reform

We want your feedback about whether insurance should be refunded for the construction of BTR developments and exempted from insurance for work to repair, renovate or alter a BTR property. This option would have the following features:

- Refund insurance for BTR construction that qualifies for tax concessions: Insurance must be purchased before work commences on a residential building project, however a building becomes a BTR property for the purposes of tax concessions on completion and an occupational certificate is issued.23 For this reason it is not feasible to exempt the construction of a BTR development from insurance. Instead, we would provide that the business that purchased the insurance could request that the premium be refunded and the insurance cancelled.

- Insurance exemption for work on existing BTR with tax concessions: In the case of an existing BTR property it should be possible to provide for work to be automatically exempt from the need to purchase insurance for work to repair, renovate or alter the property, because the BTR status of the building can be confirmed at the time the contract for the work is entered into.

- No refund or exemption for work on mix of BTR and non-BTR homes: We propose that refunds or exemptions be applicable only where all of the work relates to BTR homes, or BTR homes in combination with other things that do not require insurance. For example, the construction or renovation of a building containing dwellings used for BTR purposes as well as commercial offices or retail space would eligible for refund or exemption. By contrast if a building contained both BTR dwellings as well as dwellings otherwise offered for sale or lease, the construction of the building would not be eligible for a premium refund (consistent with current practice for mixed use buildings), and contracts for renovation and alteration work would not be exempt from insurance.

Research published by CBRE in 2021 indicated “the aggregate size of the market is currently estimated to exceed $10 billion with an additional $3-5 billion in the pipeline currently under consideration or at various stages of due diligence” with Sydney accounting for 25% of the national market24. Despite that market size, there are not yet any BTR developments that have qualified for the NSW tax concessions. Since the tax concession become available on 31 December 2020, 22 applications have been received by Revenue NSW25. Of these 16 were declined because they had less than 50 dwellings and 2 were categorised as boarding housing rather than BTR. Based on information known at the time of drafting this paper 4 applications may be assessed as eligible upon construction completion.

Costs, risks, benefits and mitigations

Benefits | Quantification or detail |

|---|---|

Reduce the cost of building and maintaining BTR developments | The ‘base rate’ cost to insure the construction of a multi-dwelling building up to 3 storeys currently adds an average of 6.250% to the cost of construction (inclusive of GST and stamp duty on the insurance). For renovation or alteration of multi-dwelling buildings of any number of storeys, the rates are 2.361% and 7.630 % respectively26. Enabling the insurance premiums to be refunded if a building is registered as a BTR development may make BTR property developments more attractive as a model for low-rise multi-dwelling complexes. Scheme data shows the average premium charged for new multi dwellings for FY2020-21 was approximately $11,000. For a BTR property with at least 50 self-contained dwellings this implies a cost saving for not requiring insurance of, on average, $550,000 for a new multi-dwelling building. |

Wider choice of contractors for work on existing BTRs | Licensed contractors would not need eligibility for insurance under HBC scheme to compete for repair, alternation and renovation works on a BTR property. For building owners that should mean a wider choice of which licensed businesses they may select to work on their building. |

Costs and risks | Quantification or mitigation |

|---|---|

Risk of uninsured losses | Whilst it is possible for dwellings within a BTR property to be sold within the period of insurance, this is mitigated by the significant financial deterrent that the owner may need to repay tax concessions. |

Insurer administration of refunds | This option would require icare HBCF and any new insurer to have administrative arrangements to process requests for the refund and cancellation of insurance. We note that icare HBCF already has arrangements in place to administer refunds and policy cancellation in other circumstances. The volume of applications is expected to be low given that most BTR developments are likely to be over 3 storeys and must contain at least 50 dwellings. |