Emotional recovery in children after a car crash

Quick reference guide for health professionals and the insurance industry to help a child recover emotionally after a car crash.

Each child’s emotional recovery after a car crash is different.

Understanding emotional responses

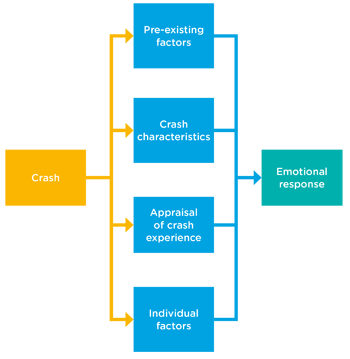

What influences emotional responses?

A child’s reaction to being in a car crash is influenced by a number of factors. These include:

- pre-existing factors - younger age, mental health problems, emotional/behavioural problems and family risk factors like low socioeconomic status

- crash characteristics - the severity of the crash, whether anyone was killed or injured

- appraisal of the crash experience - thinking they might die, or feeling intense fear (not necessarily related to the actual severity of the crash)

- individual factors - difficulty regulating distress, use of avoidance coping strategies like distraction and lack of emotional support from significant others

How responses change with age and time

Responses to a car crash vary by the age of the child and can change over time:

Immediate responses | Acute responses | Chronic responses |

|---|---|---|

Examples:

| Examples:

| Examples:

|

How often? | How often? | How often? |

Influenced by: | Influenced by: | |

Recovering

Initial emotional responses are common, but most children are resilient, and any distress will usually resolve quickly (within a couple of weeks).

Some children will have emotional responses that persist a little longer, but they too will eventually recover.

Only a very small number of children will develop sustained long-term symptoms from a car crash.

Below is a simple step-by-step guide to helping a child (and their family) recover.

1. Provide universal interventions

Universal interventions are usually provided by ambulance or hospital staff or the GP.

Universal interventions are what should be given to all children and families immediately following a car crash. These include:

- psychological first aid

- education

- social support

Do not provide the following universal interventions:

- psychological debriefing models: there is some evidence that it is of no benefit, and in some cases can lead to poorer outcomes

- medication: pharmacotherapy should not be offered as a preventative universal intervention

Psychological first aid

Psychological first aid is generally offered relatively soon after a car crash and can be provided by first responders (eg ambulance) and hospital staff. Psychological first aid is not psychological counselling or debriefing. It involves:

- practical care and support helping to address basic needs including safety

- listening without any pressure on the child to talk

- comforting and helping the child to feel calm

- connecting the child with social and emotional support

Education

In many situations, the more informed parents and children are, the better they feel.

The information should be age-appropriate and should include:

- common emotional responses, with an emphasis on the changing nature of reactions

- likely recovery

- effective coping strategies

- advice on how to get more help and how to know if further help is needed

Our how to help your child is a great place to start. It explains what children can think, feel or do after an accident and suggests ways parents can help (and where to get extra help if needed).

The After the Injury website is designed for parents, and provides information, tools and resources to support them to help their child to recover from injury.

Social support

Advise parents to seek out social support networks, and to draw on family and friends for comfort and practical assistance.

2. Screen, then watch and wait

Screening should be done by a registered healthcare professional (eg GP, nurse, psychologist) with experience in working with children.

Screening for risk can be done in the days and weeks after the crash and is recommended for up to six months. This is known as watchful waiting.

Your screening will help you determine if the child is at high or low risk of developing psychological injuries and what actions you should take.

For younger children (2-6 years old)

The recommended screening tool is the Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale-Early Screener.

The PEDS-ES can be used within two weeks after the crash, but can also be administered later.

The PEDS-ES is available at Kramer et al (2013).

For school-aged children

The Child Trauma Screening Questionnaire (CTSQ) is useful with children from seven years up. It can be used within two weeks after the crash, or later.

There are a number of other screening tools available.

What to do if screened low or high risk

If the child is considered low risk:

- Continue to monitor emotional responses and re-screen at 3-6 months. This will track whether any initial emotional responses resolve and will identify any delayed onset or escalation in symptoms.

If the child is considered high risk:

- In the early days and weeks, monitor the emotional responses. This will track if the responses resolve naturally, stay the same or get worse.

- You should re-screen at 1 month after the car crash

- If screening still indicates high risk, refer for an assessment by a psychologist or psychiatrist with training and experience in trauma treatment for children and adolescents

Involve family and caregivers

Family members should be incorporated into each stage of this process and can provide information relevant to screening.

Seek information directly from the child as well as their parents, rather than relying solely on parental assessments.

Parents can under-report children’s internalising symptoms. However in some circumstances parents are the only feasible source, for example with very young children.

Remember that screening is not a substitute for clinical assessment by a trained mental health professional.

3. Refer for assessment and intervention if needed

If the child or adolescent has been screened as high risk, they need to be referred to a mental health practitioner (eg psychologist or psychiatrist) with training and experience working with children, for treatment.

Recommended treatments

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy is the recommended treatment for children older than 6 years diagnosed with PTSD following a car crash.

Treatment must be tailored to the developmental needs of the child and not be a modified version of an adult treatment.

Parents/caregivers should be involved in therapy, at least initially, and individual therapy is preferred over group therapy.

Treatments to apply with caution

Pharmacotherapy should not be offered as a routine first treatment or adjunct to trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy.

Pharmacotherapy may be useful for some children, but this needs to be determined on a case-by-case basis by an appropriately experienced and qualified medical practitioner.

While promising, the effectiveness of eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing for children with PTSD has not yet been reliably established.

For children less than 6 years old

Because the evidence base is not strong, definite recommendations for interventions are not yet possible.

However, this situation is changing with very promising evidence for a specially modified trauma-focussed cognitive behaviour therapy for children aged from 3 to 6 years (Scheeringa et al., 2011).

Attachment-based treatments are generally more applicable and appropriate for the very young.

There is also some good evidence in very young children for child-parent psychotherapy which is a trauma-focussed attachment-based treatment (Lieberman et al., 2005).

Any mental health intervention with young children and infants should be provided by a healthcare provider with specialist training and knowledge beyond that required for school-aged children.

Further information

Other resources

More information about ASD, PTSD and their treatment can be found on the Phoenix Australia website. In particular, there is a guide for practitioners working with children and adolescents and some booklets for children and adolescents

The Healthcare Toolbox provides information and resources on trauma informed care. It includes tools and resources for practitioners , as well as well as handouts and resources for children and parents.

Diagnostic criteria for ASD and PTSD

A small number of children may develop a psychological injury after a car crash.

The most common traumatic reactions following a car crash are short-term (less than 1 month post-crash) acute stress disorder (ASD) or longer term (greater than 1 month post-crash) post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The diagnostic criteria is described below:

Acute Stress Disorder (ASD)

- Exposure to a potentially traumatic event

- Experience multiple symptoms (eg intrusive thoughts, negative mood, dissociation, avoidance and hyper-arousal)

- Symptoms persist from three days to one month after the event

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Exposure to a potentially traumatic event

- One intrusive symptom, plus one avoidance symptom, plus two negative alterations in mood or cognition, plus two hyper-arousal symptoms.

- Symptoms are evident for at least one month after the event.

PTSD adjusted for younger children (6 and under)

- Exposure to a potentially traumatic event

- One intrusive symptom, plus one avoidance or negative cognition symptom, plus two hyper-arousal symptoms

- Symptoms are evident for at least one month after the event

References for this quick reference guide

- Kenardy, J., Spence, S., & Macleod, A. (2006). Screening for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in children after accidental injury. Pediatrics. 118, 1002-1009.

- Kramer, D.N., Hertli, M. & Landolt, M.A. (2013). Evaluation of an early risk screener for PTSD in preschool children after accidental injury. Pediatrics, 132, e945-e951.

- Lieberman AF, Van Horn P, Ippen CG. (2005) Toward evidence-based treatment: child-parent psychotherapy with preschoolers exposed to marital violence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 44, 1241-8.

- Saylor CF, Swenson CC, Reynolds SS, & Taylor M. (1999). The Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale: a brief screening measure for young children exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 28, 70–8.

- Scheeringa, M. S., Weems, C. F., Cohen, J. A., Amaya-Jackson, L., & Guthrie, D. (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three through six year-old children: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 52, 853–860.

This quick reference guide was developed for SIRA by Professor Justin Kenardy and Dr Katrina Moss, from the Recover Injury Research Centre, The University of Queensland.